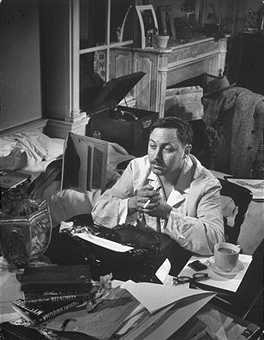

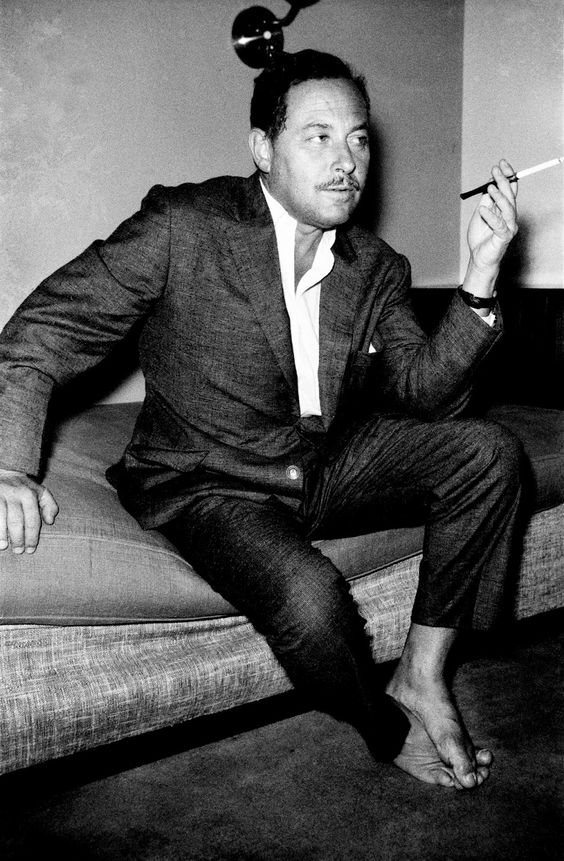

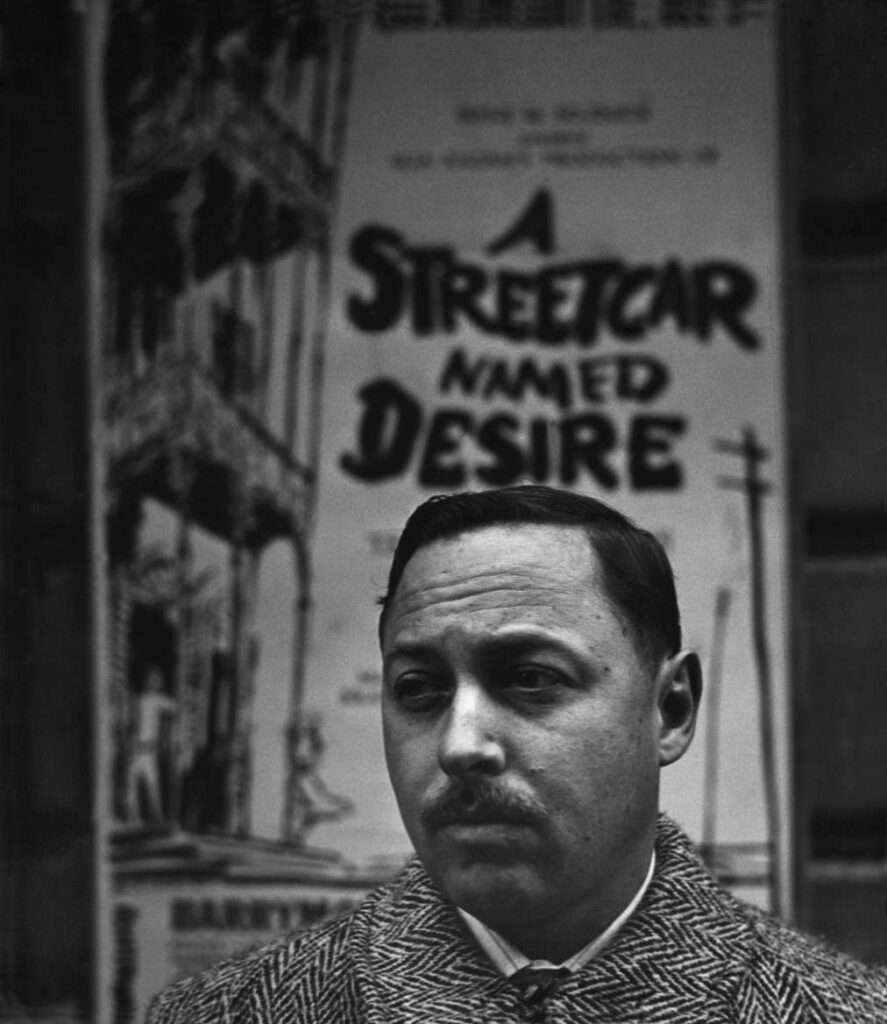

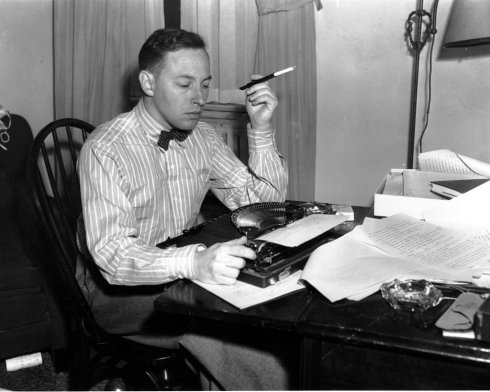

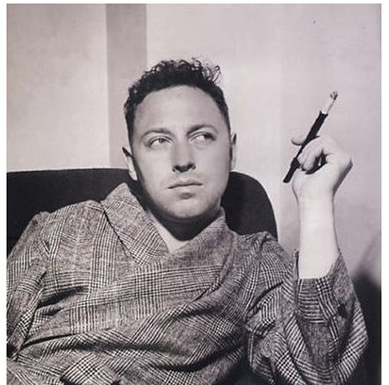

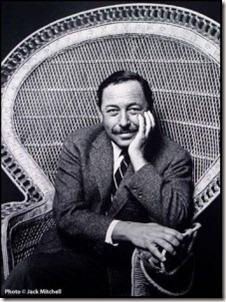

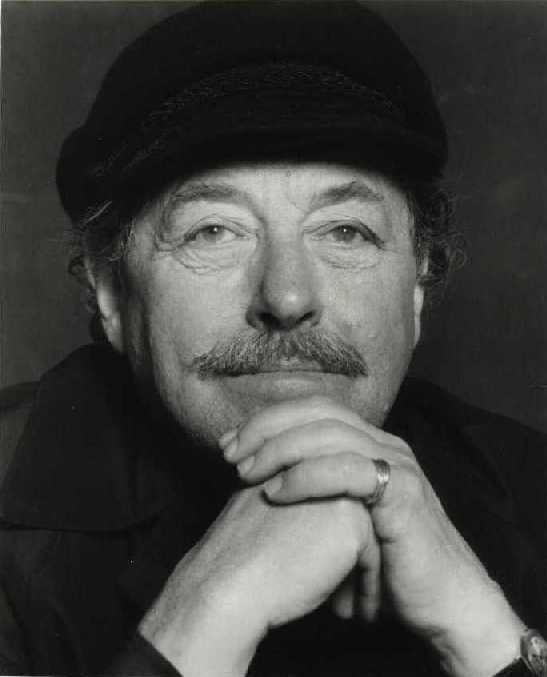

Thomas Lanier “Tennessee” Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983) was an American playwright and author of many stage classics. Along with Eugene O’Neill and Arthur Miller he is considered among the three foremost playwrights in 20th century American drama.

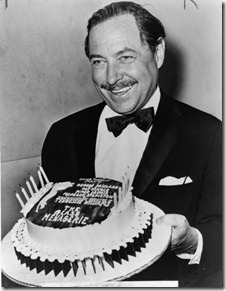

After years of obscurity, he became suddenly famous with The Glass Menagerie (1944), closely reflecting his own unhappy family background. This heralded a string of successes, including A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959). His later work attempted a new style that did not appeal to audiences, and alcohol and drug dependence further inhibited his creative output. His drama A Streetcar Named Desire is often numbered on the short list of the finest American plays of the 20th century alongside Long Day’s Journey into Night and Death of a Salesman.

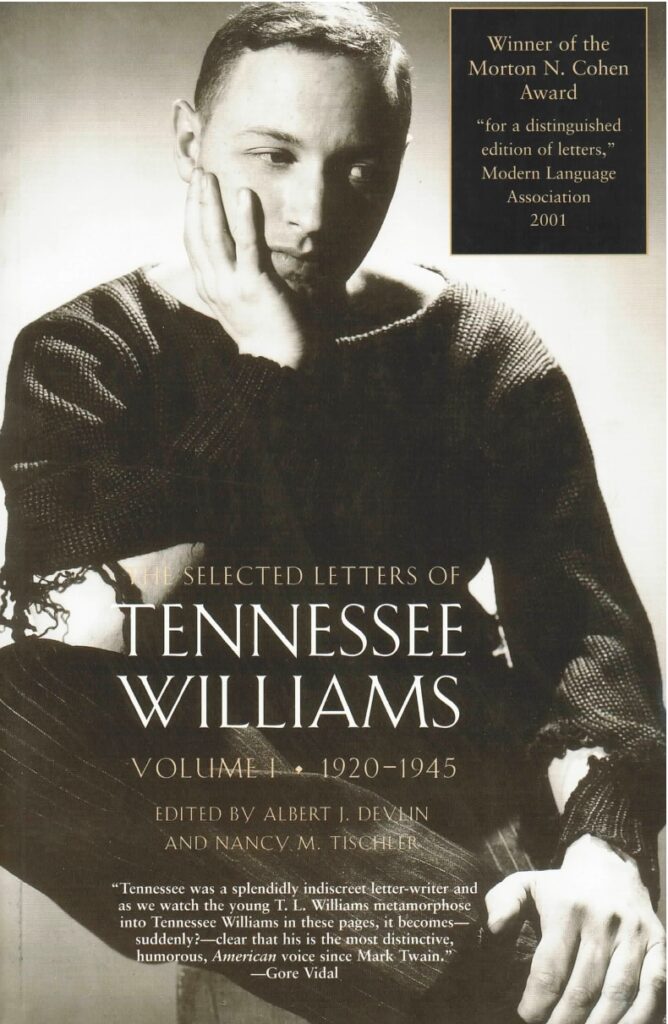

Much of Williams’ most acclaimed work was adapted for the cinema. He also wrote short stories, poetry, essays and a volume of memoirs. In 1979, four years before his death, Williams was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame.

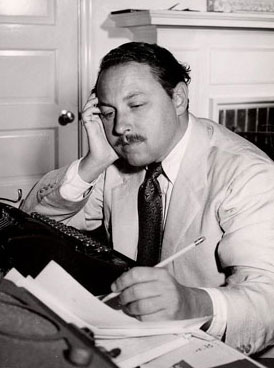

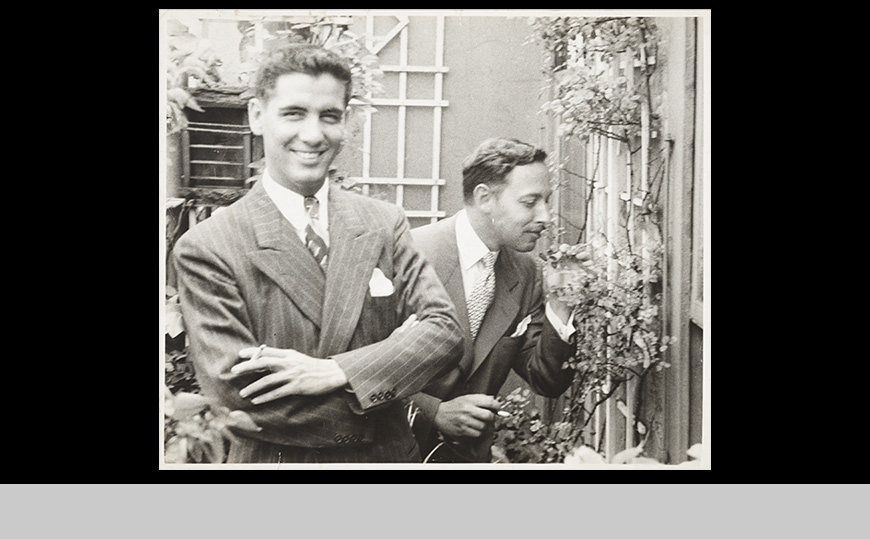

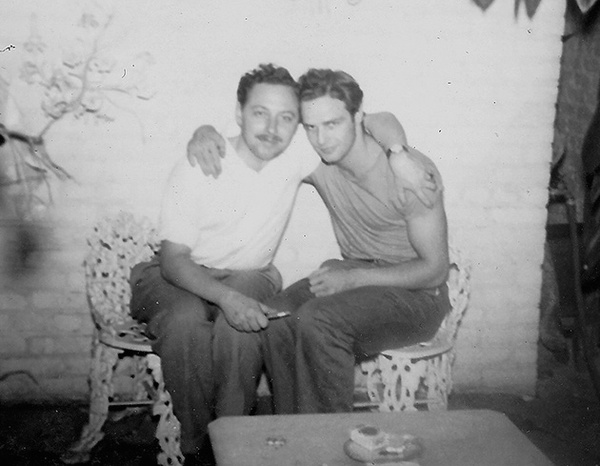

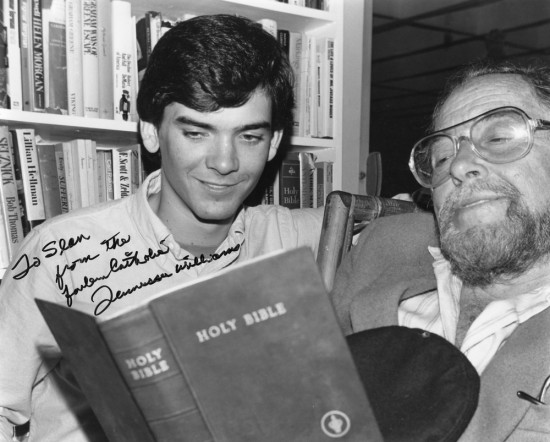

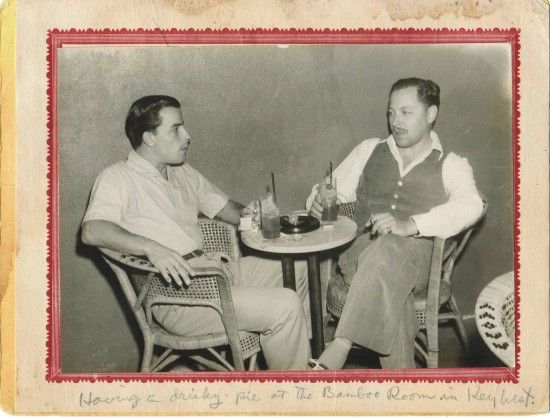

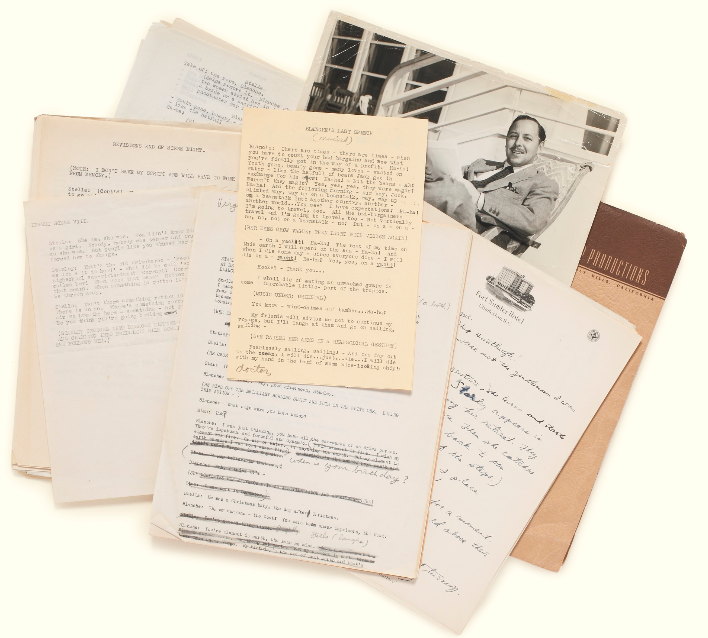

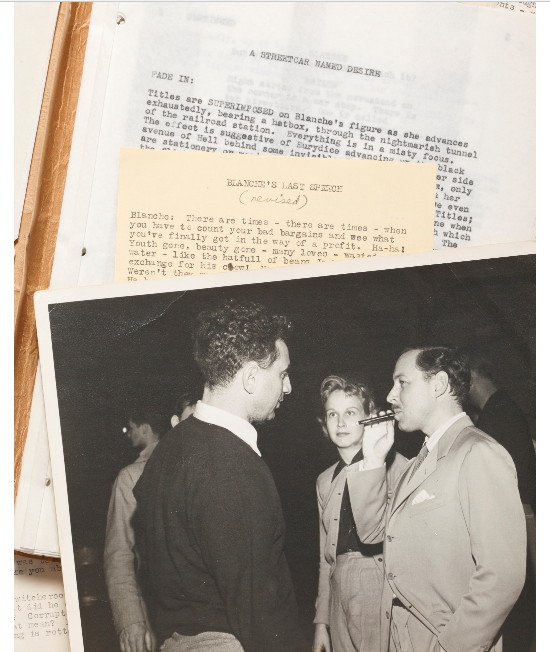

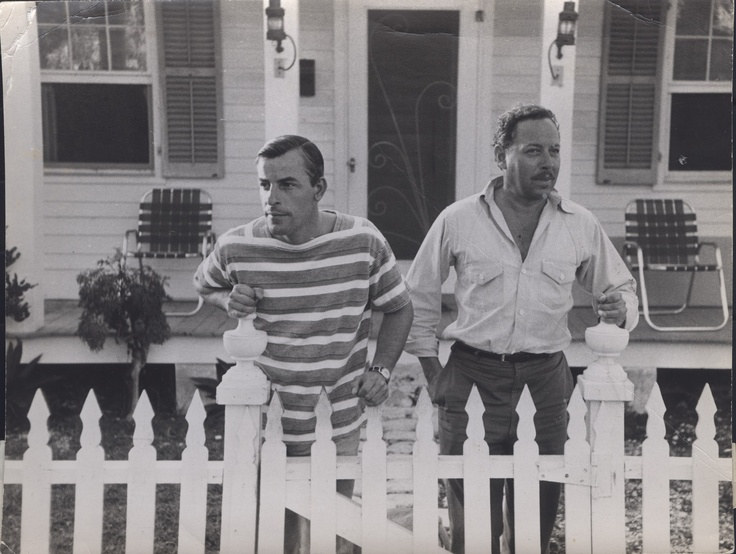

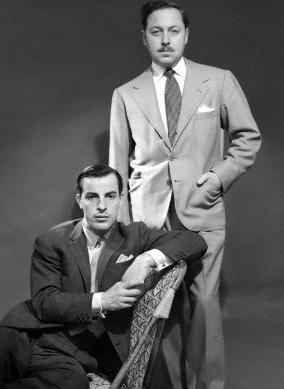

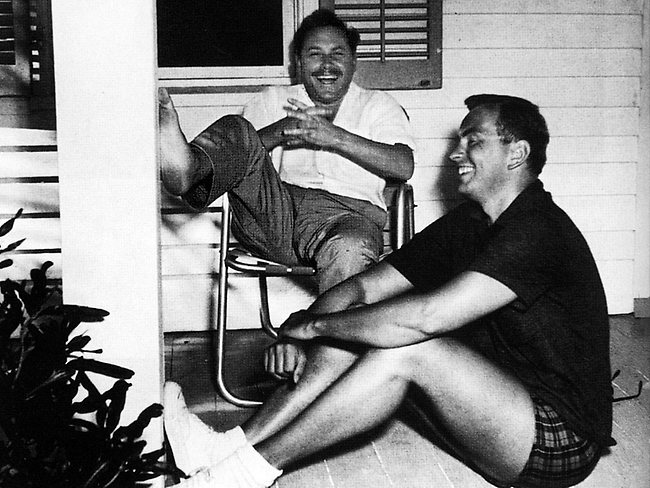

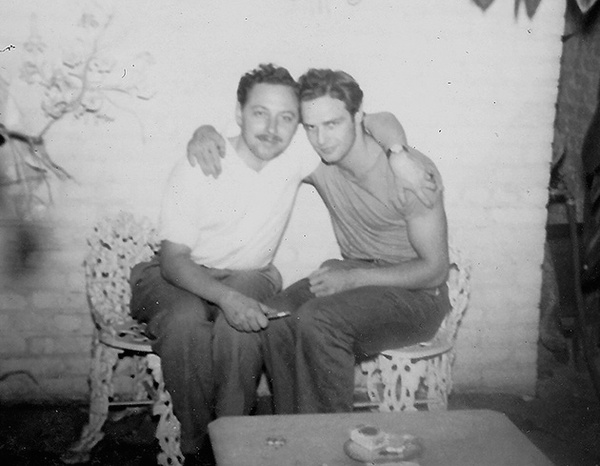

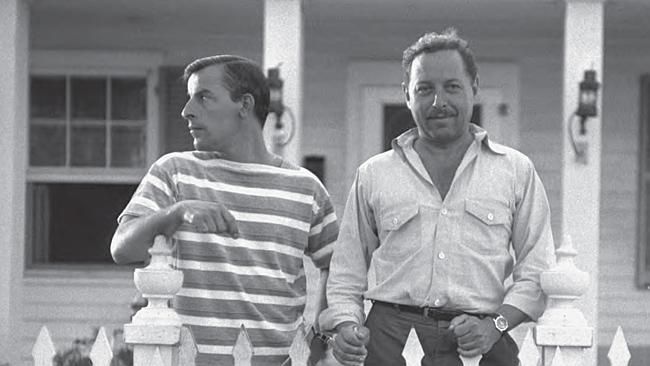

Tennessee and Marlon Brandon

Like many authors, Williams wasn’t adept at expressing himself outside of his work, but he sometimes evinced a startling degree of tough self-awareness. “The real fact is that no one means a great deal to me,” he said in a 1945 interview. “I’m gregarious and like to be around people, but almost anybody will do.” Williams was at his “most alert, eloquent, humorous, vulnerable, and forthright when talking about the one pure thing in his life: his work.” But what was pure? His writing was the bridge he tried to build between his besmirched, original-sin self—the self that loved the temporary pleasures of sex, but no doubt considered it “dirty”—and the self that sought purification in a world other than this one. Indeed, the world he represents in his 1943 short play, “The Purification,” is a plea for that very thing—the expiation of guilt and sin. The pathos one finds in that piece, Williams’s only verse play, grows out of the fact that the protagonist has murdered his sister—his one true love. Amidst the poetry, blood stops blood. (Siblings as the source of life and death and the imagination is also the theme of Williams’s underrated 1973 play, “Outcry.”) There was no end to Williams’s guilt, remorse, and anger for having survived his sister, in particular, and his family as a whole. No survivor is ever free of his history of disaster.

Early Life

Thomas Lanier Williams III was born in Columbus, Mississippi of English, Welsh, and Huguenot ancestry, the second child of Edwina Dakin (1884-1980) and Cornelius Coffin (C. C.) Williams (1879-1957). His father was an alcoholic traveling shoe salesman who spent much of his time away from home. His mother, Edwina, was the daughter of Rose O. Dakin, a music teacher and the Reverend Walter Dakin, an Episcopal priest who was assigned to a parish in Clarksdale, Mississippi shortly after Williams’ birth. Williams’ early childhood was spent in the parsonage there. Williams had two siblings, sister Rose Isabel Williams (1909-1996) and brother Walter Dakin Williams  (1919-2008).

As a small child Williams suffered from a case of diphtheria which nearly ended his life, leaving him weak and virtually confined to his house during a period of recuperation that lasted a year. At least in part as a result of his illness, he was less robust as a child than his father wished. Cornelius Williams, a descendant of hardy east-Tennessee pioneer stock (hence Williams’ professional name), had a violent temper and was a man prone to use his fists. He regarded his son’s effeminacy with disdain, and his mother Edwina, locked in an unhappy marriage, focused her overbearing attention almost entirely on her frail young son. Many critics and historians note that Williams found inspiration for much of his writing in his own dysfunctional family.

When Williams was eight years old his father was promoted to a job at the home office of the International Shoe Company in St. Louis, Missouri. His mother’s continual search for what she considered to be an appropriate address, as well as his father’s heavy drinking and loudly turbulent behaviour, caused them to move numerous times around the city. He attended Soldan High School, a setting he referred to in his play The Glass Menagerie. Later he studied at University City High School. At age 16, Williams won third prize (five dollars) for an essay published in Smart Set entitled, “Can a Good Wife Be a Good Sport?” A year later, his short story “The Vengeance of Nitocris” was published in the August 1928 issue of the magazine Weird Tales. That same year he first visited Europe with his grandfather.

Literary Influences

Williams’ writings include mention of some of the poets and writers he most admired in his early years: Hart Crane, Anton Chekhov (from the age of ten), William Shakespeare, D. H. Lawrence, August Strindberg, William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, Emily Dickinson. In later years the list grew to include William Inge, James Joyce, and Ernest Hemingway; of Hemingway, he said “[his] great quality, aside from his prose style, is this fearless expression of brute nature.

Personal Life

Throughout his life Williams remained close to his sister Rose who was diagnosed with schizophrenia as a young woman. In 1943, as her behaviour became increasingly disturbing, she was subjected to a lobotomy with disastrous results and was subsequently institutionalized for the rest of her life. As soon as he was financially able to, Williams had her moved to a private institution just north of New York City where he often visited her. He gave her a percentage interest in several of his most successful plays, the royalties from which were applied toward her care. The devastating effects of Rose’s illness may have contributed to Williams’ alcoholism and his dependence on various combinations of amphetamines and barbiturates.

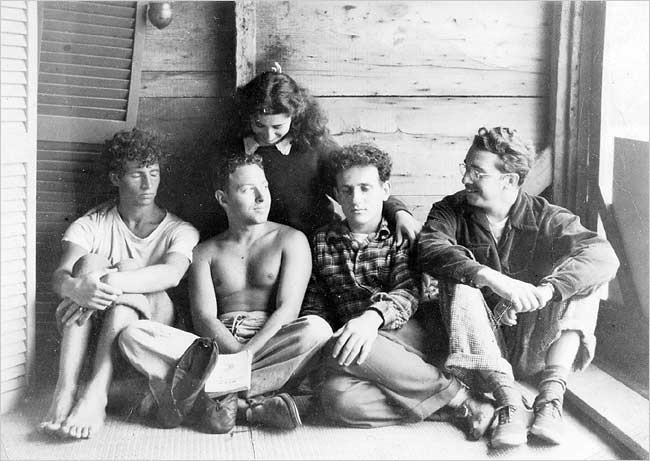

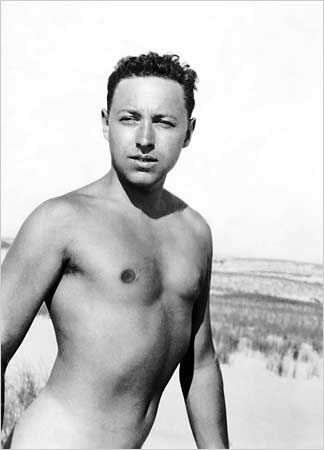

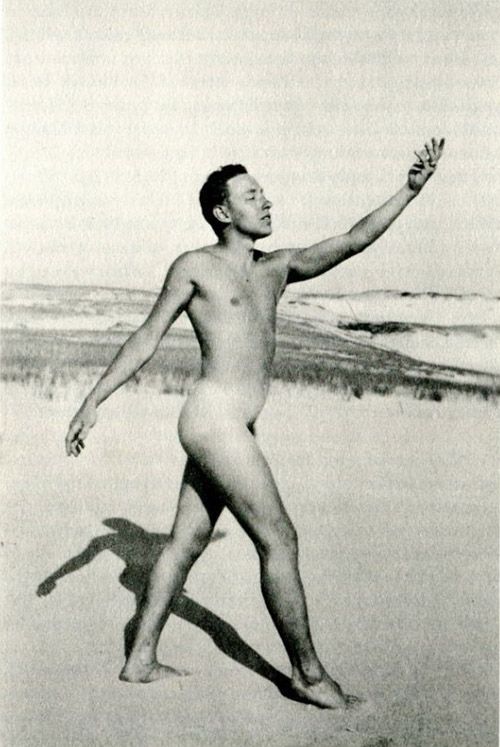

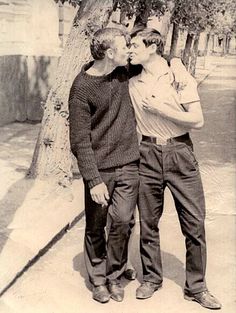

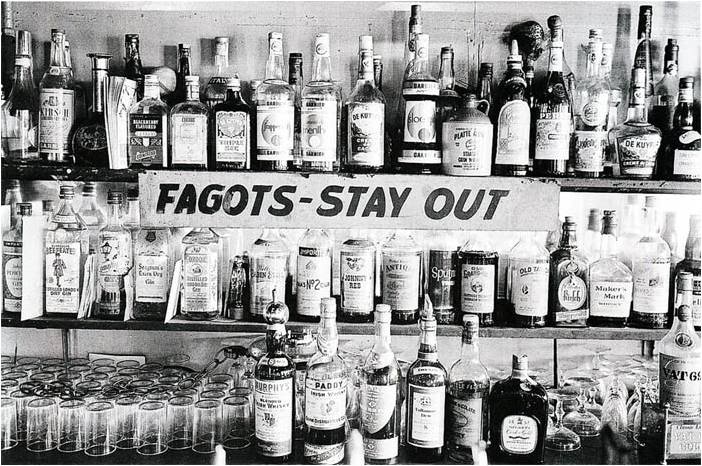

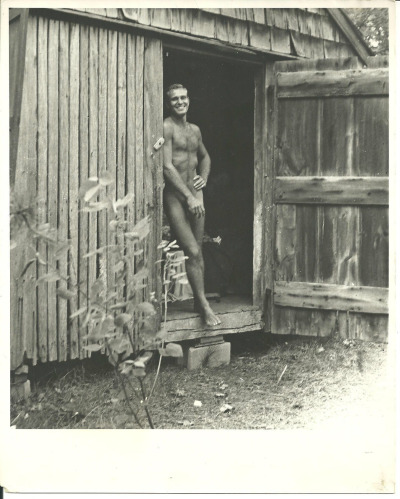

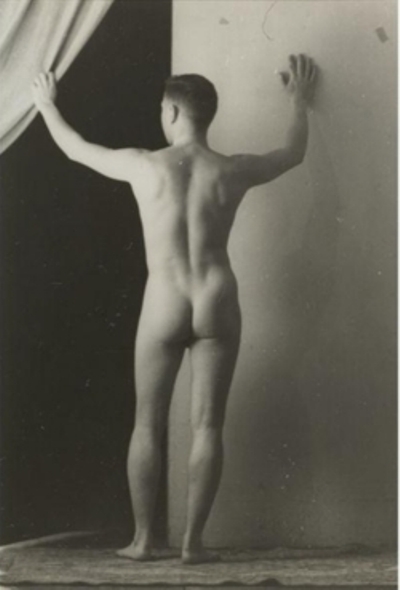

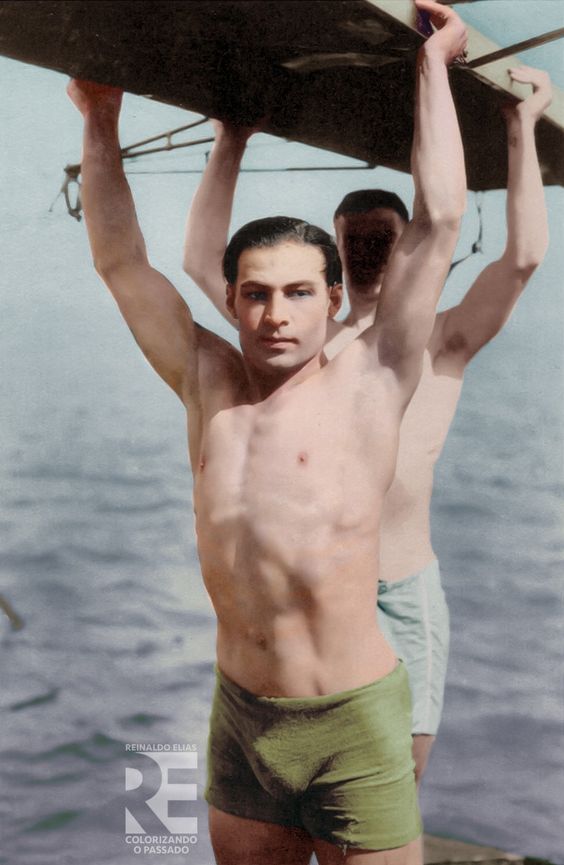

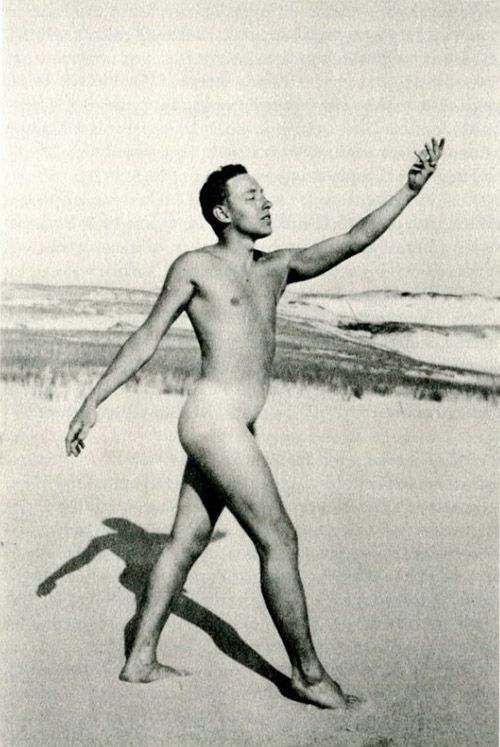

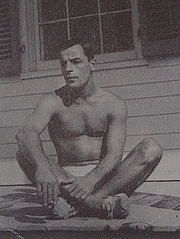

After some early attempts at relationships with women, by the late 1930s Williams had finally accepted his homosexuality. In New York he joined a gay social circle which included fellow writer and close friend Donald Windham (1920-2010) and his then partner Fred Melton. In the summer of 1940 Williams initiated an affair with Kip Kiernan (1918-1944), a young Canadian dancer he met in Provincetown, Massachusetts. When Kiernan left him to marry a woman he was distraught, and Kiernan’s death four years later at 26 delivered another heavy blow.

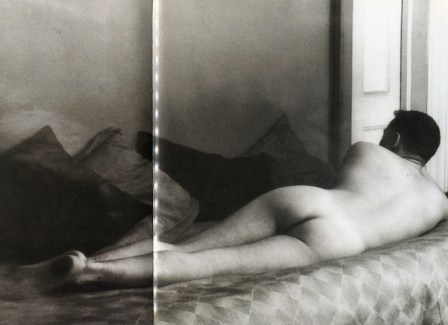

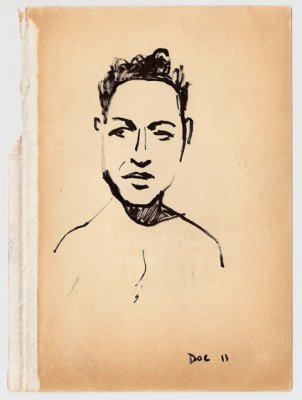

Kip Kiernan (1918-1944)

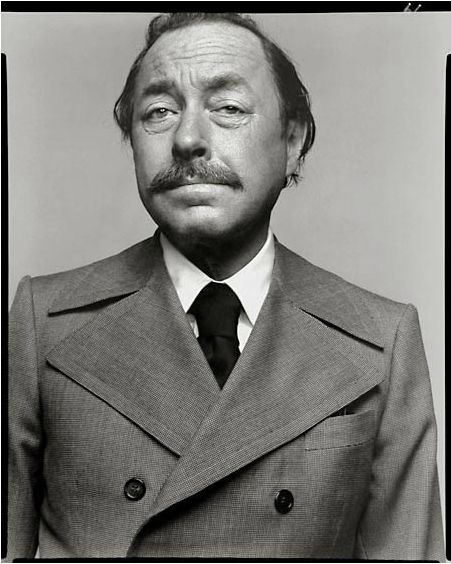

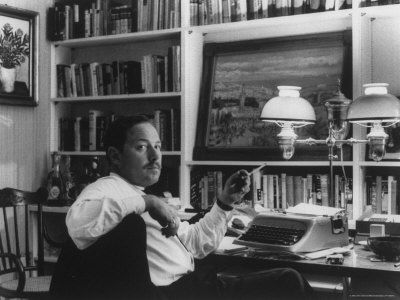

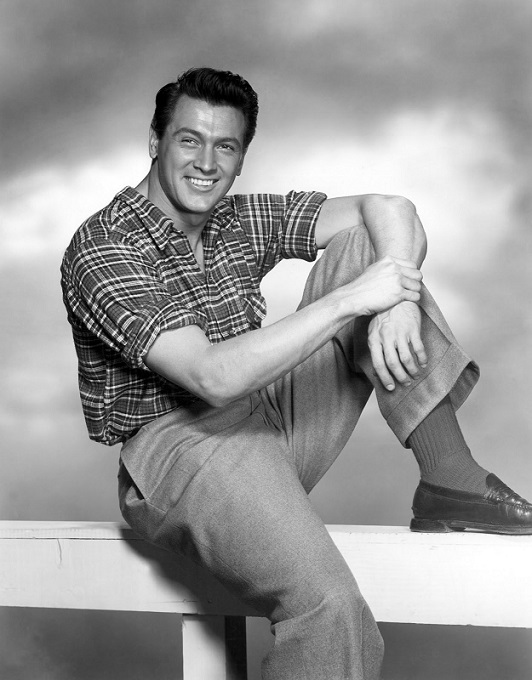

On a 1945 visit to Taos, New Mexico, Williams met Pancho Rodrguez y Gonz¡lez, a hotel clerk of Mexican heritage. RodrÃguez was, by all accounts, a loving and loyal companion. However, he was also prone to jealous rages and excessive drinking, and so the relationship was a tempestuous one. Nevertheless, in February 1946 RodrÃguez left New Mexico to join Williams in his New Orleans apartment. They lived and travelled together until late 1947 when Williams ended the affair. Rodrguez and Williams remained friends, however, and were in contact as late as the 1970s. Williams spent the spring and summer of 1948 in Rome in the company of a teenaged Italian boy, called “Rafaello” in Williams’ Memoirs, to whom he provided financial assistance for several years afterwards, a situation which planted the seed of Williams’ first novel, The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone. When he returned to New York that spring, he met and fell in love with Frank Merlo (1922-1963), an occasional actor of Sicilian heritage who had served in the U.S. Navy in World War II.

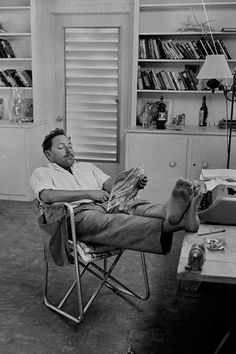

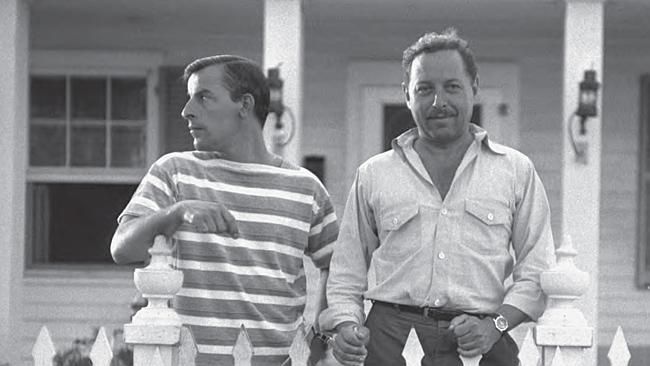

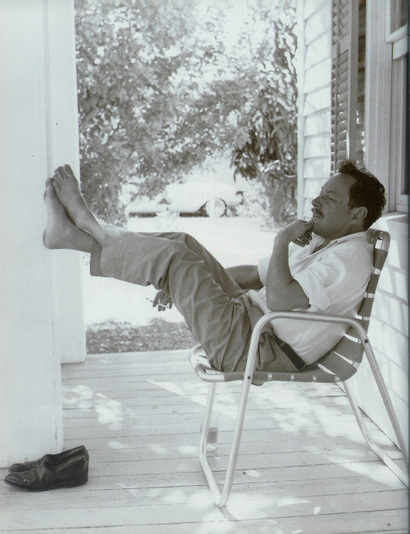

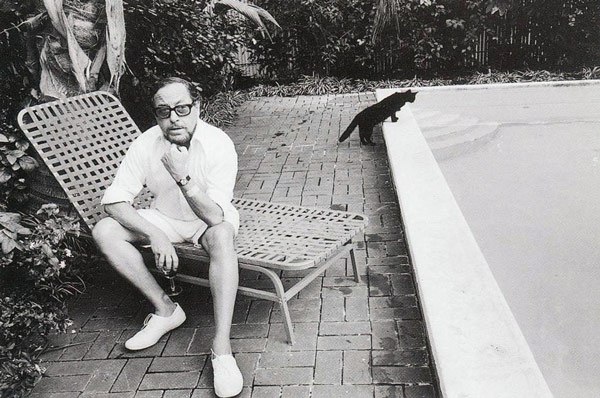

This one enduring romantic relationship of Williams’ life lasted 14 years until infidelities and drug abuse on both sides ended it. Merlo, who became Williams’ personal secretary, taking on most of the details of their domestic life, provided a period of happiness and stability as well as a balance to the playwright’s frequent bouts with depression and the fear that, like his sister Rose, he would fall into insanity. Their years together, in an apartment in Manhattan and a modest house in Key West, Florida, were Williams’ happiest and most productive. Shortly after their breakup, Merlo was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer and Williams returned to take care of him until his death on September 20, 1963.

Frank Merlo (1922–1963)

As he had feared, in the years following Merlo’s death Williams was plunged into a period of nearly catatonic depression and increasing drug use resulting in several hospitalizations and commitments to mental health facilities. He submitted to injections by Dr. Max Jacobson known popularly as Dr. Feelgood who used increasing amounts of amphetamines to overcome his depression and combined these with prescriptions for the sedative Seconal to relieve his insomnia. During this time, influenced by his brother Dakin a Roman Catholic convert, Williams joined the Catholic church. He was never truly able to recoup his earlier success, or to entirely overcome his dependence on prescription drugs.

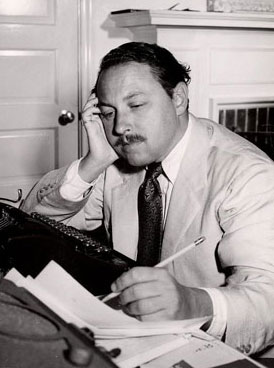

Career

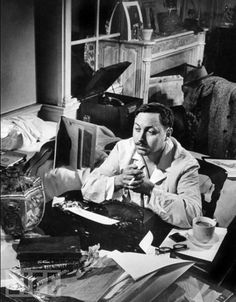

As Williams was struggling to gain production and an audience for his work in the late 1930s, he worked at a string of menial jobs that included a stint as caretaker on a chicken ranch in Laguna Beach, California. In 1939, with the help of his agent Audrey Wood, Williams was awarded a $1,000 grant from the Rockefeller Foundation in recognition of his play Battle of Angels. It was produced in Boston, Massachusetts in 1940 and was poorly received.

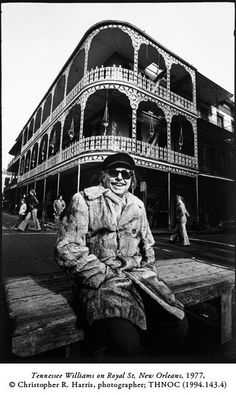

Using some of the Rockefeller funds, Williams moved to New Orleans in 1939 to write for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a federally funded program begun by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to put people to work. Williams lived for a time in New Orleans’ French Quarter, including 722 Toulouse Street, the setting of his 1977 play Vieux Carré. The building is now part of The Historic New Orleans Collection. The Rockefeller grant brought him to the attention of the Hollywood film industry and Williams received a six-month contract as a writer from the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film studio, earning $250 weekly.

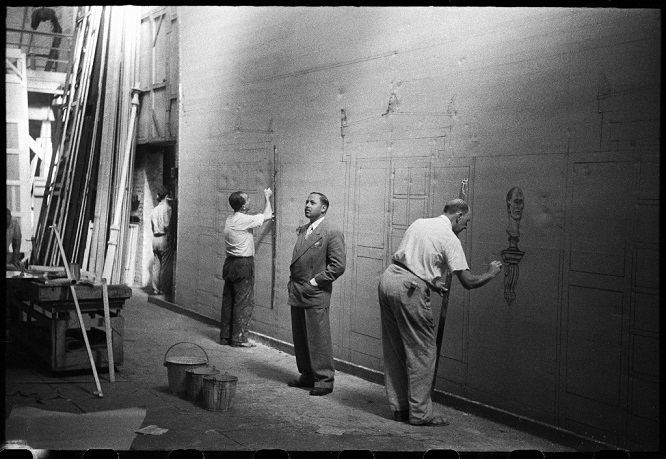

During the winter of 1944–45, his memory play The Glass Menagerie developed from his 1943 short story “Portrait of a Girl in Glass”, was produced in Chicago and garnered good reviews. It moved to New York where it became an instant hit and enjoyed a long Broadway run. Elia Kazan (who directed many of Williams’s greatest successes) said of Williams: “Everything in his life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is in his life.” The Glass Menagerie won the award for the best play of the season, the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award.

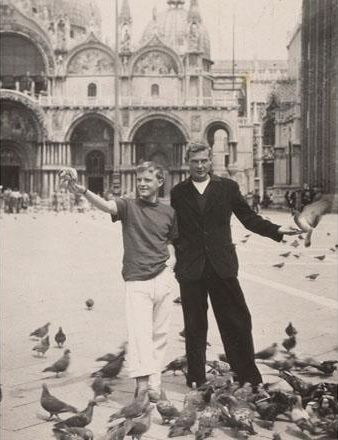

The huge success of his next play, A Streetcar Named Desire, cemented his reputation as a great playwright in 1947. During the late 1940s and 1950s, Williams began to travel widely with his partner Frank Merlo (1922 – September 21, 1963), often spending summers in Europe. He moved often to stimulate his writing, living in New York, New Orleans, Key West, Rome, Barcelona, and London. Williams wrote, “Only some radical change can divert the downward course of my spirit, some startling new place or people to arrest the drift, the drag.”

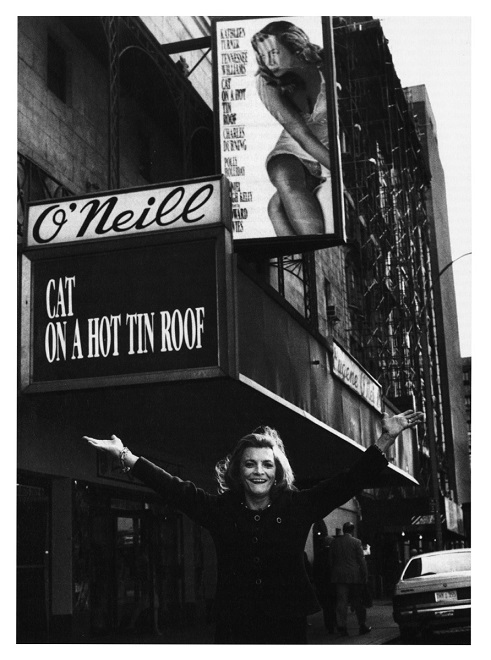

Between 1948 and 1959 Williams had seven of his plays produced on Broadway: Summer and Smoke (1948), The Rose Tattoo (1951), Camino Real (1953), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955), Orpheus Descending (1957), Garden District (1958), and Sweet Bird of Youth (1959). By 1959, he had earned two Pulitzer Prizes, three New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards, three Donaldson Awards, and a Tony Award.

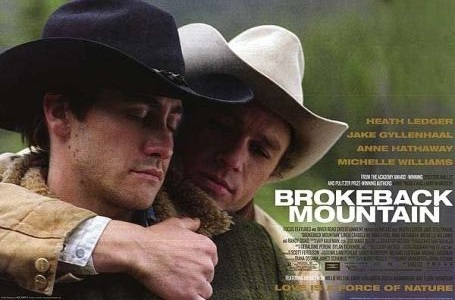

Williams’s work reached wider audiences in the early 1950s when The Glass Menagerie and A Streetcar Named Desire were adapted into motion pictures. Later plays also adapted for the screen included Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, The Rose Tattoo, Orpheus Descending, The Night of the Iguana, Sweet Bird of Youth, and Summer and Smoke.

After the extraordinary successes of the 1940s and 1950s, he had more personal turmoil and theatrical failures in the 1960s and 1970s. Although he continued to write every day, the quality of his work suffered from his increasing alcohol and drug consumption, as well as occasional poor choices of collaborators. In 1963, his partner Frank Merlo died.

Consumed by depression over the loss, and in and out of treatment facilities while under the control of his mother and brother Dakin, Williams spiraled downward. His plays Kingdom of Earth (1967), In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969), Small Craft Warnings (1973), The Two Character Play (also called Out Cry, 1973), The Red Devil Battery Sign (1976), Vieux Carré (1978), Clothes for a Summer Hotel (1980), and others were all box office failures. Negative press notices wore down his spirit. His last play, A House Not Meant to Stand, was produced in Chicago in 1982. Despite largely positive reviews, it ran for only 40 performances.

In 1974, Williams received the St. Louis Literary Award from the Saint Louis University Library Associates. In 1979, four years before his death, he was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame

Death

On February 25, 1983, Williams was found dead in his suite at the Elyse Hotel in New York at age 71. The medical examiner’s report indicated that he choked to death on the cap from a bottle of eye drops he frequently used. An amended coroners report indicates that his use of drugs and alcohol may have contributed to his death by suppressing his gag reflex. Prescription drugs, including barbiturates, were found in the room. The cause of death the coroner reported as “Seconal intolerance.” He had used Seconal with alcohol as his drugs of choice for most of his life.

Williams had long told his friends he wanted to be buried at sea at approximately the same place as Hart Crane, a poet he considered to be one of his most significant influences. Contrary to his expressed wishes, but at his brother Dakin Williams’ insistence, Williams was interred in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri.

Williams left his literary rights to The University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee, an Episcopal Church in the United States school, in honor of his grandfather, Walter Dakin, an alumnus of the university. The funds support a creative writing program. When his sister Rose died in 1996 after many years in a mental institution, she bequeathed $7 million  from her part of the Williams estate to The University of the South as well.

Posthumous Recognition

From February 1 to July 21, 2011, to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth, the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, the home of Williams’ archive, exhibited 250 of his personal items. The exhibit, entitled “Becoming Tennessee Williams,” included a collection of Williams manuscripts, correspondence, photographs and artwork. In late 2009, Williams was inducted into the Poets’ Corner at the Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine. Performers who took part in his induction included Vanessa Redgrave, John Guare, Eli Wallach, Sylvia Miles, Gregory Mosher, and Ben Griessmeyer. The Tennessee Williams Theatre in Key West, Florida, is named for him.

At the time of his death, Williams had been working on a final play, In Masks Outrageous and Austere, which attempted to reconcile certain forces and facts of his own life, a theme which ran throughout his work, as Elia Kazan had said. As of September 2007, author Gore Vidal was in the process of completing the play, and Peter Bogdanovich was slated to direct its Broadway debut. Â The play finally received its world premiere in New York City in April 2012, directed by David Schweizer and starring Shirley Knight as Babe.

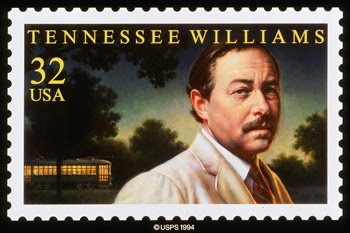

The rectory of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Columbus, Mississippi, where Williams’s grandfather Dakin was rector at the time of Williams’s birth, was moved to another location in 1993 for preservation, and was newly renovated in 2010 for use by the City of Columbus as the Tennessee Williams Welcome Center. Williams’s literary legacy is represented by the literary agency headed by Georges Borchardt. Williams was honored by the U.S. Postal Service on a stamp in 1994 as part of its literary arts series. Williams is honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame

Since 1986, the Tennessee Williams New Orleans Literary Festival has been held annually in New Orleans, LA, in commemoration of the playwright. The festival takes place at the end of March to coincide with Williams’ birthday.

Bibliography

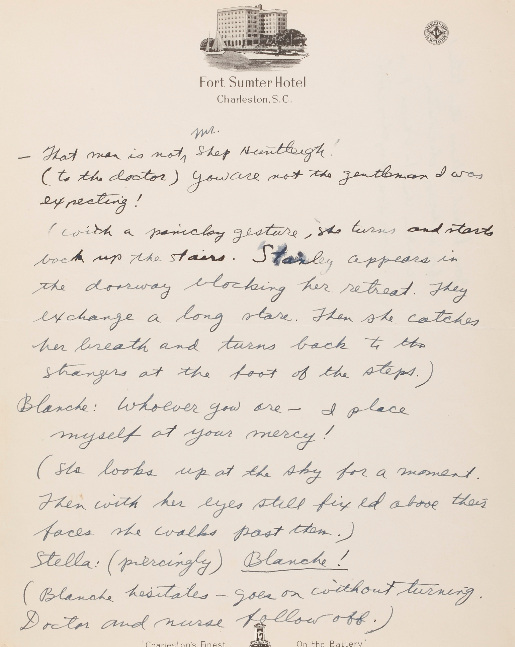

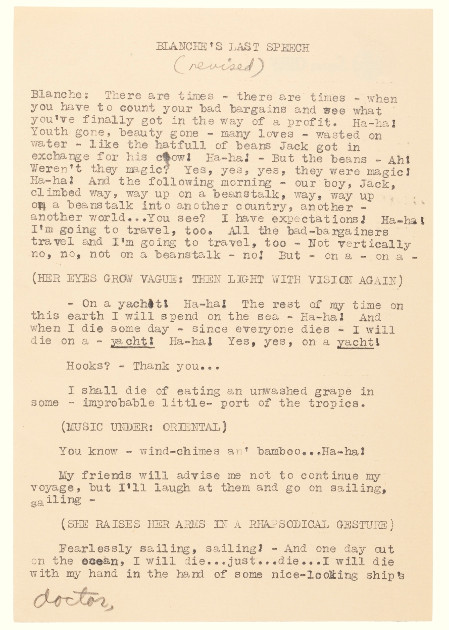

Characters in his plays are often seen as representations of his family members. Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie was understood to be modeled on Rose. Some biographers believed that the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire is also based on her.

Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie was generally seen to represent Williams’ mother, Edwina. Characters such as Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and Sebastian in Suddenly, Last Summer were understood to represent Williams himself. In addition, he used a lobotomy operation as a motif in Suddenly, Last Summer.

The Pulitzer Prize for Drama was awarded to A Streetcar Named Desire in 1948 and to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955. These two plays were later filmed, with great success, by noted directors Elia Kazan (Streetcar) with whom Williams developed a very close artistic relationship, and Richard Brooks (Cat). Both plays included references to elements of Williams’ life such as homosexuality, mental instability, and alcoholism. Although The Flowering Peach by Clifford Odets was the preferred choice of the Pulitzer Prize jury in 1955 and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was at first considered the weakest of the five shortlisted nominees, Joseph Pulitzer Jr., chairman of the Board, had seen Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and thought it worthy of the drama prize. The Board went along with him after considerable discussion.

Williams wrote The Parade, or Approaching the End of a Summer when he was 29 and worked on it sporadically throughout his life. A semi-autobiographical depiction of his 1940 romance with Kip Kiernan in Provincetown, Massachusetts, it was produced for the first time on October 1, 2006 in Provincetown by the Shakespeare on the Cape production company, as part of the First Annual Provincetown Tennessee Williams Festival.

His last play went through many drafts as he was trying to reconcile what would be the end of his life. There are many versions of it, but it is referred to as In Masks Outrageous and Austere.

Works

Characters in his plays are often seen as representations of his family members. Laura Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie is thought to be modeled on his sister Rose. Some biographers believed that the character of Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire also is based on her and that the mental deterioration of Blanche’s character is inspired by Rose’s mental health struggles.

Amanda Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie generally was taken to represent Williams’s mother Edwina. Characters such as Tom Wingfield in The Glass Menagerie and Sebastian in Suddenly, Last Summer were understood to represent Williams himself. In addition, he used a lobotomy as a motif in Suddenly, Last Summer.

The Pulitzer Prize for Drama was awarded to A Streetcar Named Desire in 1948 and to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1955. These two plays later were adapted as highly successful films by noted directors Elia Kazan (Streetcar), with whom Williams developed a very close artistic relationship, and Richard Brooks (Cat). Both plays included references to elements of Williams’s life such as homosexuality, mental instability, and alcoholism.

Although The Flowering Peach by Clifford Odets was the preferred choice of the Pulitzer Prize jury in 1955, and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was at first considered the weakest of the five shortlisted nominees, Joseph Pulitzer Jr., chairman of the Board, had seen Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and thought it worthy of the drama prize. The Board went along with him after considerable discussion.

Williams wrote The Parade, or Approaching the End of a Summer when he was 29, and worked on it sporadically throughout his life. A semi-autobiographical depiction of his 1940 romance with Kip Kiernan in Provincetown, Massachusetts, it was produced for the first time on October 1, 2006, in Provincetown by the Shakespeare on the Cape production company. This was part of the First Annual Provincetown Tennessee Williams Festival. Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1981) is also based on his memories of Provincetown in the 1940s.

His last play went through many drafts as he was trying to reconcile what would be the end of his life. There are many versions of it, but it is referred to as In Masks Outrageous and Austere.

Apprentice plays

- Candles to the Sun (1936)

- Fugitive Kind (1937)

- Spring Storm (1937)

- Me Vaysha (1937)

- Not About Nightingales (1938)

- Battle of Angels (1940)

- I Rise in Flame, Cried the Phoenix (1941)

- You Touched Me (1945)

- Stairs to the Roof (1947)

Major Plays

- The Glass Menagerie (1944)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1947)

- Summer and Smoke (1948)

- The Rose Tattoo (1951)

- Camino Real (1953)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955)

- Orpheus Descending (1957)

- Suddenly, Last Summer (1958)

- Sweet Bird of Youth (1959)

- Period of Adjustment (1960)

- The Night of the Iguana (1961)

- The Eccentricities of a Nightingale (1962, rewriting of Summer and Smoke)

- The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore (1963)

- The Mutilated (1965)

- The Seven Descents of Myrtle (1968, aka Kingdom of Earth)

- In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel (1969)

- Will Mr. Merriweather Return from Memphis? (1969)

- Small Craft Warnings (1972)

- The Two-Character Play (1973)

- Out Cry (1973, rewriting of The Two-Character Play)

- The Red Devil Battery Sign (1975)

- This Is (An Entertainment) (1976)

- Vieux Carré (1977)

- A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur (1979)

- Clothes for a Summer Hotel (1980)

- The Notebook of Trigorin (1980)

- Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1981)

- A House Not Meant to Stand (1982)

- In Masks Outrageous and Austere (1983)

Gallery

Novels

- The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone (1950, adapted for films in 1961 and 2003)

- Moise and the World of Reason (1975)

Screenplays and Teleplays

- The Glass Menagerie (1950)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

- The Rose Tattoo (1955)

- Baby Doll (1956)

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958)

- Suddenly, Last Summer (1959)

- The Fugitive Kind (1959)

- Ten Blocks on the Camino Real (1966)

- Boom! (1968)

- Stopped Rocking and Other Screenplays (1984)

- The Loss of a Teardrop Diamond (2009; screenplay from 1957)

Short Stories

- “The Vengeance of Nitocris” (1928)

- “The Field of Blue Children” (1939)

- “Oriflamme” (1944)

- “The Resemblance Between a Violin Case and a Coffin” (1951)

- One Arm and Other Stories (1948)

- “One Arm”

- “The Malediction”

- “The Poet”

- “Chronicle of a Demise”

- “Desire and the Black Masseur”

- “Portrait of a Girl in Glass”

- “The Important Thing”

- “The Angel in the Alcove”

- “The Field of Blue Children”

- “The Night of the Iguana”

- “The Yellow Bird”

- Hard Candy: A Book of Stories (1954)

- Three Players of a Summer Game

- Two on a Party

- The Resemblance between a Violin Case and a Coffin

- Hard Candy

- Rubio y Morena

- The Mattress by the Tomato Patch

- The Coming of Something to the Widow Holly

- The Vine

- The Mysteries of the Joy Rio

- The Knightly Quest: a Novella and Four Short Stories (1966)

- The Knightly Quest

- Mama’s Old Stucco House

- Man Bring This Up Road

- The Kingdom of Earth

- “Grand”

- Eight Mortal Ladies Possessed: a Book of Stories (1974)

- Happy August the Tenth

- The Inventory at Fontana Belle

- Miss Coynte of Greeme

- Sabbatha and Solitude

- Completed

- Oriflamme

- Tent Worms (1980)

- It Happened the Day the Sun Rose (1981), published by Sylvester & Orphanos

- Collected Stories (1985) (New Directions)

One-Act Plays

Williams wrote over 70 one-act plays during his lifetime. The one-acts explored many of the same themes that dominated his longer works. Williams’s major collections are published by New Directions in New York City.

- American Blues (1948)

- Mister Paradise and Other One-Act Plays (2005)

- Dragon Country: a book of one-act plays (1970)

- The Traveling Companion and Other Plays (2008)

- The Magic Tower and Other One-Act Plays (2011)

- At Liberty (1939)

- The Magic Tower (1936)

- Me, Vashya (1937)

- Curtains for the Gentleman (1936)

- In Our Profession (1938)

- Every Twenty Minutes (1938)

- Honor the Living (1937)

- The Case of the Crushed Petunias (1941)

- Moony’s Kid Don’t Cry (1936)

- The Dark Room (1939)

- The Pretty Trap (1944)

- Interior: Panic (1946)

- Kingdom of Earth (1967)

- I Never Get Dressed Till After Dark on Sundays (1973)

- Some Problems for the Moose Lodge (1980)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton and Other Plays (1946 and 1953)

- «Something wild…» (introduction) (1953)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1946 and 1953)

- The Purification (1946 and 1953)

- The Lady of Larkspur Lotion (1946 and 1953)

- The Last of My Solid Gold Watches (1946 and 1953)

- Portrait of a Madonna (1946 and 1953)

- Auto-da-Fé (1946 and 1953)

- Lord Byron’s Love Letter (1946 and 1953)

- The Strangest Kind of Romance (1946 and 1953)

- The Long Goodbye (1946 and 1953)

- At Liberty (1946)

- Moony’s Kid Don’t Cry (1946)

- Hello from Bertha (1946 and 1953)

- This Property Is Condemned (1946 and 1953)

- Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen… (1953)

- Something Unspoken (1953)

- Now the Cats with Jeweled Claws and Other One-Act Plays (2016)

- A Recluse and His Guest (1982)

- Now the Cats with Jeweled Claws (1981)

- Steps Must Be Gentle (1980)

- Ivan’s Widow (1982)

- This Is the Peaceable Kingdom (1981)

- Aimez-vous Ionesco? (c.1975)

- The Demolition Downtown (1971)

- Lifeboat Drill (1979)

- Once in a Lifetime (1939)

- The Strange Play (1939)

- The Theatre of Tennessee Williams, Volume VI

- The Theatre of Tennessee Williams, Volume VII

Poetry and Non-fiction

- In the Winter of Cities (1956)

- Androgyne, Mon Amour (1977)

- The Collected Poems of Tennessee Williams (2002)

- Memoirs (1975)

- New Selected Essays: Where I Live (2009)

Selected Works

- Gussow, Mel and Holditch, Kenneth, eds. Tennessee Williams, Plays 1937–1955 (Library of America, 2000) ISBN978-1-883011-86-4.

- Spring Storm

- Not About Nightingales

- Battle of Angels

- I Rise in Flame, Cried the Phoenix

- From 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1946)

- 27 Wagons Full of Cotton

- The Lady of Larkspur Lotion

- The Last of My Solid Gold Watches

- Portrait of a Madonna

- Auto-da-Fé

- Lord Byron’s Love Letter

- This Property Is Condemned

- The Glass Menagerie

- A Streetcar Named Desire

- Summer and Smoke

- The Rose Tattoo

- Camino Real

- From 27 Wagons Full of Cotton (1953)

- “Something Wild”

- Talk to Me Like the Rain and Let Me Listen

- Something Unspoken

- Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

- Gussow, Mel and Holditch, Kenneth, eds. Tennessee Williams, Plays 1957–1980 (Library of America, 2000) ISBN978-1-883011-87-1.

- Orpheus Descending

- Suddenly, Last Summer

- Sweet Bird of Youth

- Period of Adjustment

- The Night of the Iguana

- The Eccentricities of a Nightingale

- The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore

- The Mutilated

- Kingdom of Earth (The Seven Descents of Myrtle)

- Small Craft Warnings

- Out Cry

- Vieux Carré

- A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur

- “Crazy Night”

After the extraordinary successes of the 1940s and 1950s, he had more personal turmoil and theatrical failures in the 1960s and 1970s. Although he continued to write every day, the quality of his work suffered. In the years following Merlo’s death in 1963, Williams descended into a period of nearly catatonic depression and increasing drug use; this resulted in several hospitalizations and commitments to mental health facilities. His doctor, Dr. Max Jacobson – known popularly as Dr. Feelgood – would give him injections in increasing amounts of amphetamines to overcome his depression. Jacobson combined these with prescriptions for the sedative Seconal to relieve his insomnia.

Tennessee Williams, Tennessee Williams – bio, gay playwright, gay plays, gay stories, gay story, American gay playwright, A Streetcar Named Desire, The Glass Menagerie, The Rose Tattoo, gay bios, gay icons, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Sweet Bird of Youth