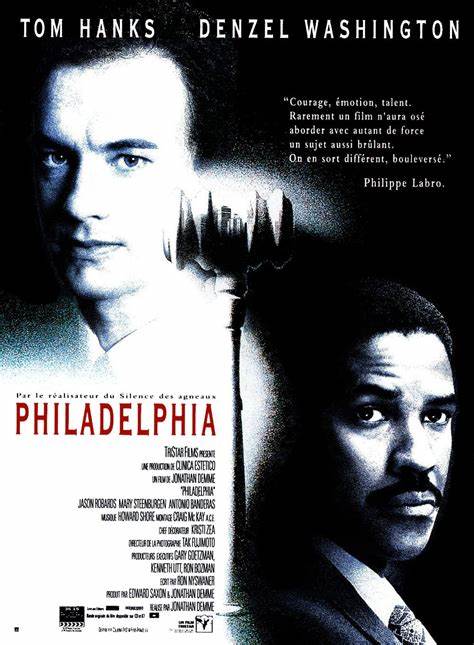

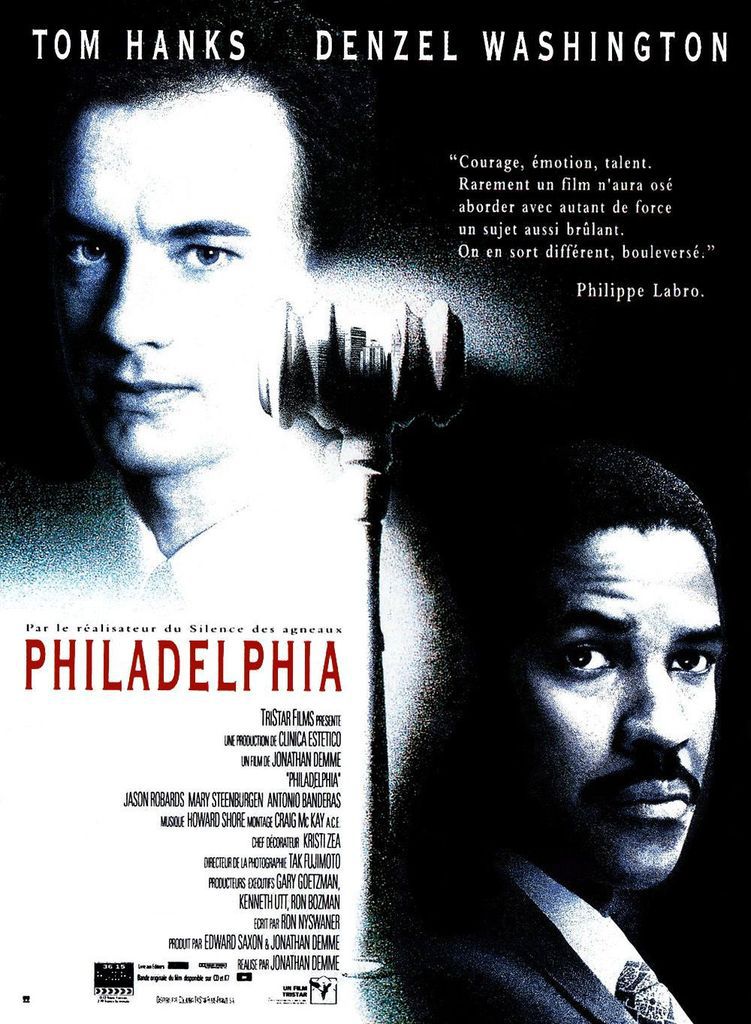

Philadelphia – 1993

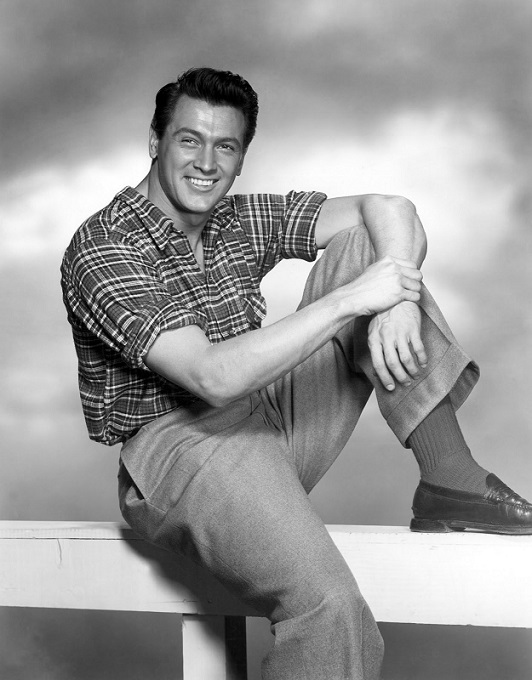

Philadelphia is a 1993 American legal drama film written by Ron Nyswaner, directed by Jonathan Demme and starring Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington. Filmed and set in its namesake city, it tells the story of gay man Andrew Beckett (Hanks) who asks lawyer Joe Miller (Washington) to help him sue his employers, who fired him after discovering he has AIDS.

Philadelphia premiered in Los Angeles on December 14, 1993 and opened in limited release on December 22, before expanding into wide release on January 14, 1994. It grossed $206.7 million worldwide, becoming the 9th highest-grossing film of 1993. It was positively received by critics for its screenplay and the performances of Washington and Hanks. For his performance as Andrew Beckett, Hanks won the Academy Award for Best Actor at the 66th Academy Awards, while the song “Streets of Philadelphia” by Bruce Springsteen won the Academy Award for Best Original Song. Nyswaner was also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, but lost to Jane Campion for The Piano. It is notable for being one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to explicitly address HIV/AIDS and homophobia, in addition to being one of the first mainstream Hollywood films to portray gay people in a positive light.

Plot

Andrew Beckett is a senior associate at the largest corporate law firm in Philadelphia. He conceals his homosexuality and his status as an AIDS patient from the other members of the firm. A partner in the firm notices a lesion on Beckett’s forehead. Although Beckett attributes the lesion to a racquetball injury, it indicates Kaposi’s sarcoma, an AIDS-defining condition.

Beckett stays home from work for several days to try to find a way to hide his lesions. He finishes the paperwork for a case he has been assigned and brings it to his office, leaving instructions for his assistants to file the paperwork the following day, which marks the end of the statute of limitations for the case. The next day, he receives a call asking for the paperwork, as the paper copy cannot be found and there are no copies on the computer’s hard drive. The paperwork is finally located in an alternative location and is filed with the court at the last moment. Beckett is called to a meeting the morning afterwards where the firm’s partners dismiss him.

Beckett believes someone deliberately hid the paperwork to give the firm an excuse to fire him and that the termination is a result of his diagnosis with AIDS as well as his sexuality. He asks ten attorneys to take his case, the last of whom is African-American personal injury lawyer Joe Miller, whom Beckett previously opposed in a different case. Miller appears uncomfortable that a man with AIDS is in his office. After declining to take the case, Miller immediately visits his doctor to find out if he could have contracted the disease. The doctor explains that the routes of HIV infection do not include casual contact.

Unable to find a lawyer willing to represent him, Beckett is compelled to act as his own attorney. While researching another case at a law library, Miller sees Beckett at a nearby table. A librarian approaches Beckett and says that he has found a case of AIDS discrimination for him. As others in the library begin to stare uneasily, the librarian suggests Beckett go to a private room. Seeing the parallels in how he has faced discrimination due to his race, Miller approaches Beckett, reviews the material he has gathered, and agrees to take the case.

As the case goes to trial, the partners of the firm take the stand, each claiming that Beckett was incompetent and that he had deliberately tried to hide his condition. The defense repeatedly suggests that Beckett brought AIDS upon himself via gay sex and is therefore not a victim. It is revealed that the partner who noticed Beckett’s lesion, Walter Kenton, previously worked with a woman who had contracted AIDS after a blood transfusion and so should have recognized the lesion as being a symptom of an AIDS-related illness. According to Kenton, the woman was an innocent victim, unlike Beckett, and he further testifies that he did not recognize Beckett’s lesion. To prove that the lesions would have been visible, Miller asks Beckett to unbutton his shirt while on the witness stand, revealing that his lesions are indeed visible and recognizable as such. Throughout the trial, Miller’s homophobia slowly disappears as he and Beckett bond from working together.

Beckett collapses and is hospitalized after Charles Wheeler, the partner he most admired, testifies against him. Another partner, Bob Seidman, confesses that he suspected Beckett had AIDS but never told anyone and didn’t allow him to explain himself, which he deeply regrets. During Beckett’s hospital stay, the jury votes in his favor, awarding him back pay, damages for pain and suffering, and punitive damages, totalling over $5 million. Miller visits the visibly failing Beckett in the hospital after the verdict and overcomes his fear enough to touch Beckett’s face. After the family leaves the room, Beckett tells his lover Miguel Alvarez that he is “ready.” At the Miller home later that night, Miller and his wife are awakened by a phone call from Alvarez, who tells them that Beckett has died. A memorial is held at Beckett’s home, where many mourners, including Miller and his family, view home movies of Beckett as a happy child.

Trailer

Cast

- Tom Hanks as Andrew “Andy” Beckett

- Denzel Washington as Joseph “Joe” Miller

- Jason Robards as Charles Wheeler

- Mary Steenburgen as Belinda Conine

- Antonio Banderas as Miguel Alvarez

- Joanne Woodward as Sarah Beckett

- Robert W. Castle as Bud Beckett

- Ann Dowd as Jill Beckett

- Adam LeFevre as Jill’s husband

- John Bedford Lloyd as Matt Beckett

- Dan Olmstead as Randy Beckett

- Lisa Summerour as Lisa Miller

- Charles Napier as Judge Lucas Garnett

- Roberta Maxwell as Judge Tate

- Roger Corman as Mr. Roger Laird

- David Drake as Bruno

- Harry Northup as Juror No. 6

- Bill Rowe as Dr. Armbruster

- Chandra Wilson as Chandra

- Daniel von Bargen as Jury Foreman

- Karen Finley as Dr. Gillman

- Robert Ridgely as Walter Kenton

- Bradley Whitford as Jamey Collins

- Ron Vawter as Bob Seidman

- Anna Deavere Smith as Anthea Burton

- Obba Babatundé as Jerome Green

- Charles Glenn as Kenneth Killcoyne

- Tracey Walter as the Librarian

- Andre B. Blake as Young Man in Pharmacy (as André B. Blake)

- Daniel Chapman as Clinic Storyteller

- Peter Jacobs as Peter / Mona Lisa

- Paul Lazar as Dr. Klenstein

- Warren Miller as Mr. Finley

- Joey Perillo as Filko

- Lauren Roselli as Iris

- Lisa Talerico as Shelby

- Kathryn Witt as Melissa Benedict

- Julius Erving as himself

- Mayor of Philadelphia Ed Rendell as himself

- The Flirtations as themselves

- Q Lazzarus as Party Singer

- Quentin Crisp as Party Guest (uncredited)

Daniel Day-Lewis was offered the role of Andrew Beckett, but turned it down. Bill Murray and Robin Williams were considered for the role of Joe Miller. John Leguizamo was offered the role of Miguel Álvarez, but turned it down to play Luigi in the film Super Mario Bros. In an interview with The New York Times in June 2022, Tom Hanks said that the film would not get made nowadays with a straight actor in a gay role, stating audiences wouldn’t “accept the inauthenticity of a straight guy playing a gay guy”. Hanks added that that was “rightly so”, stating “One of the reasons people weren’t afraid of that movie is that I was playing a gay man”.

Inspiration

The events in the film are similar to the events in the lives of attorneys Geoffrey Bowers and Clarence Cain. Bowers was an attorney who, in 1987, sued the law firm Baker McKenzie for wrongful dismissal in one of the first AIDS discrimination cases. Cain was an attorney for Hyatt Legal Services who was fired after his employer found out he had AIDS. He sued Hyatt in 1990, and won just before his death.

In 1994, shortly after the film’s release, Scott Burr, a former attorney with the Philadelphia firm of Kohn, Nast and Graf, sued his previous employer for illegally terminating him upon finding out that he was HIV positive. Like the defendants in the film, the firm claimed that it fired him for incompetence without knowing about his health. The parties settled the lawsuit for an undisclosed amount after three weeks of trial. Burr continued to practice law prior to his death in 2020.

Bowers’ family sued the writers and producers of the film. A year after Bowers’ death in 1987, a producer, Scott Rudin, had interviewed the Bowers family and their lawyers, and, according to the family, promised compensation for the use of Bowers’ story as a basis for a film. Family members asserted that 54 scenes in the movie were so similar to events in Bowers’s life that some of them could only have come from their interviews. However, the defense said that Rudin had abandoned the project after hiring a writer and did not share any information the family had provided. The lawsuit was settled after five days of testimony. Although terms of the agreement were not released, the defendants did admit that “the film ‘was inspired in part'” by Bowers’ story.

Gallery

Release

Philadelphia premiered in Los Angeles on December 14, 1993 and opened in limited release in four theaters on December 22, before expanding into wide release on January 14, 1994. The L.A. premiere was a benefit for AIDS Project Los Angeles, which netted $250,000 APLA Chair Steve Tisch told the LA Times.

The film was the first Hollywood big-budget, big-star film to tackle the issue of AIDS in the U.S. (following the TV movie And the Band Played On) and signaled a shift in Hollywood films toward more realistic depictions of people in the LGBT community. According to a Tom Hanks interview for the 1995 documentary The Celluloid Closet, he was cast in the role due to his non-intimidating screen persona in order to allow for audiences to sympathize with a gay, HIV-positive character. However, scenes showing more affection between him and Banderas were cut, including one with him and Banderas in bed together. The DVD edition, produced by Automat Pictures, includes this scene.

Philadelphia was released on VHS on June 29, 1994 and on DVD on September 10, 1997. Philadelphia was later released as a limited-edition Blu-ray through Twilight Time on May 14, 2013. In conjunction with the film’s 25th anniversary, the film was released on 4K Blu-Ray on November 27, 2018. The screenplay was also republished in a novelization by writer Christopher Davis in 1994.

Reception

Philadelphia was originally released on December 22, 1993, in a limited opening of only four theaters, and had a weekend gross of $143,433 with an average of $35,858 per theater. The film expanded its release on January 14, 1994, to 1,245 theaters and went to number one at the US box office, grossing $13.8 million over the 4-day Martin Luther King Jr. Day weekend, averaging $11,098 per theater. The film stayed at number 1 the following weekend, earning another $8.8 million.

In its 14th weekend, the weekend after the Oscars, the film expanded to 888 theaters, and saw its gross increase by 70 percent, making $1.9 million and jumping from number 15 the previous weekend (when it made $1.1 million from 673 theaters), to return to the top ten ranking at number 8 that weekend.

Philadelphia eventually grossed $77.4 million in North America and $129.2 million overseas for a total of $206.7 million worldwide against a budget of $26 million, making it a significant box office success, and becoming the 12th highest-grossing film in the U.S. of 1993.

On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 81% based on 62 reviews, with an average rating of 6.9/10. The site’s critical consensus reads: “Philadelphia indulges in some unfortunate clichés in its quest to impart a meaningful message, but its stellar cast and sensitive direction are more than enough to compensate.” Metacritic gave the film a weighted average score of 66 out of 100, based on 21 critics, indicating “generally favorable reviews.” Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of “A” on an A+ to F scale.

In a contemporary review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert gave the film three and a half out of four stars and said that it is “quite a good film, on its own terms. And for moviegoers with an antipathy to AIDS but an enthusiasm for stars like Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington, it may help to broaden understanding of the disease. It’s a ground breaker like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967), the first major film about an interracial romance; it uses the chemistry of popular stars in a reliable genre to sidestep what looks like controversy.”

Christopher Matthews from the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote “Jonathan Demme’s long-awaited Philadelphia is so expertly acted, well-meaning and gutsy that you find yourself constantly pulling for it to be the definitive AIDS movie.” James Berardinelli from ReelViews wrote “The story is timely and powerful, and the performances of Hanks and Washington assure that the characters will not immediately vanish into obscurity.” Rita Kempley from The Washington Post wrote “It’s less like a film by Demme than the best of Frank Capra. It is not just canny, corny and blatantly patriotic, but compassionate, compelling and emotionally devastating.”

Streaming

‘Philadelphia’ is currently available to rent, purchase, or stream via subscription on Apple iTunes, DIRECTV, Microsoft Store, Redbox, Google Play Movies, Amazon Video, AMC on Demand, Vudu, and YouTube. (as of 01/28/2023)

Buy the Disc at Amazon

Philadelphia – 1993

Philadelphia – 1993, Philadelphia, gaymovies, Tom Hanks, Denzel Washington, Jason Robards, Mary Steenburgen, Antonio Banderas, gay drama, AIDS, Gayfilms, Gay Cinema, Gay Artists, gay stories, Aids Stories, Gay Friends