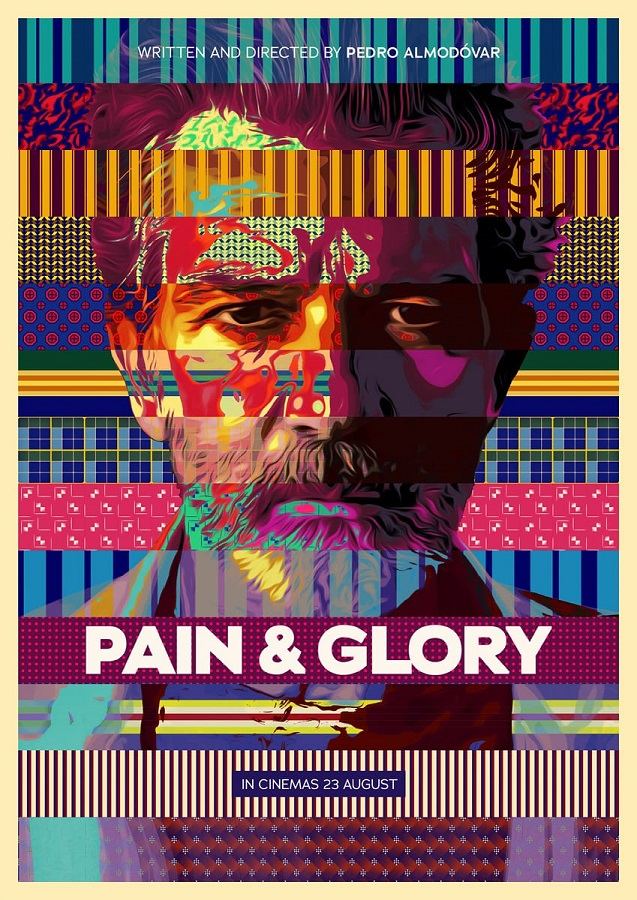

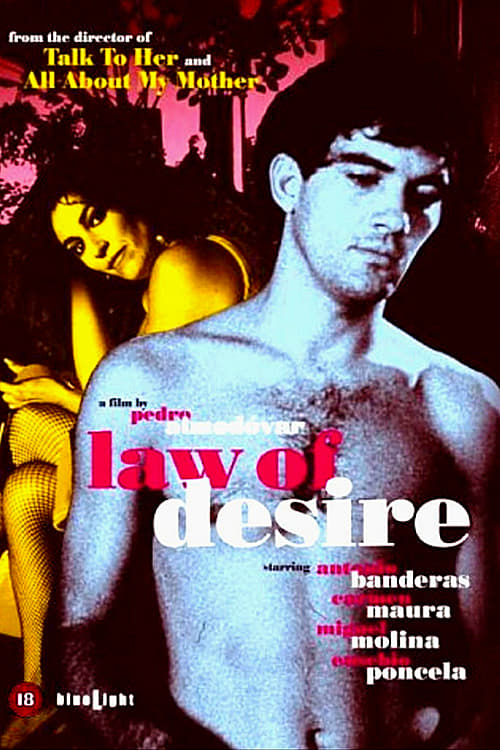

Law of Desire (Spanish: La ley del deseo) is a 1987 Spanish comedy thriller[1] film written and directed by Pedro Almodóvar. Starring Eusebio Poncela as Pablo, Carmen Maura as Tina and Antonio Banderas as Antonio. It was the first film Almodóvar made independently with his own production company El Deseo.

The story focuses on a complex love triangle between three men. Pablo, a successful gay film director, disappointed in his relationship with his young lover, Juan, concentrates in a new project, a monologue starring his transgender sister, Tina. Antonio, an uptight young man, falls possessively in love with the director, and in his passion would stop at nothing to obtain the object of his desire. The relationship between Pablo and Antonio is at the core of the film; however, the story of Pablo’s sister, Tina, plays a strong role in the plot.

Shot in the later part of 1986, Law of Desire was Almodóvar’s first work centered on homosexual relationships. He considers Law of Desire the key film in his life and career. It follows the more serious tone set by Almodóvar’s previous film, Matador, exploring the unrestrained force of desire. The film’s themes include love, loss, gender, family, sexuality, and the close link between life and art.

Law of Desire was met with general positive reactions from film critics, and it was a hit with audiences, becoming Almodóvar’s most successful film up to that point. It toured many international film festivals, winning the Teddy Award in Berlin, and it made Almodóvar known internationally.

Elements from Law of Desire grew into the basis for three later films: Carmen Maura appears in a stage production of Jean Cocteau’s The Human Voice, which inspired Almodóvar’s next film, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown; Tina’s confrontation scene with an abusive priest formed a partial genesis for Bad Education; and a short film version of Cocteau’s The Human Voice, starring Tilda Swinton, the first film by Almodóvar to be acted in English.

Trailer

Plot

Pablo Quintero is a successful gay film and theatrical director whose latest work, The Paradigms of the Mussel, has just been released. At the opening night party, he discusses with his much younger lover, Juan, their summer plans. Pablo would stay in Madrid working on a new project, while Juan would leave for his hometown in the south to work in a bar and stay with his family. Pablo is in love with Juan, but he realizes that his love is not returned with the intensity he desires.

Pablo is very close to his transgender (referred to as transsexual in the film) sister Tina, a struggling actress. Tina has recently been abandoned by her lesbian lover, a model, who left her in charge of her ten-year-old daughter Ada. Frustrated in her relationship with men, Tina dedicates her time to Ada, being a loving surrogate mother. The precocious Ada does not miss her cold mother. She is happier living with Tina and spending time with Pablo, on whom she has a crush. Tina, Ada, and Pablo form an unusual family unit. Pablo looks after them both. For his next project, Pablo writes an adaptation of Cocteau’s monologue-play The Human Voice, to be performed by his sister.

At the play’s opening night, Pablo meets Antonio, a young man who has been obsessed with the director since he watched the gay theme film The Paradigms of the Mussel. At the end of the evening, they go home together and have sex. For Antonio this is his first homosexual experience, while Pablo considers it just a lusty episode. Pablo is still in love with his long-time lover, Juan. Antonio misunderstands Pablo’s intentions and takes their encounter as a relationship. He soon reveals his possessive character as a lover.

Antonio comes across a love letter addressed to Pablo, signed by Juan, but which in fact was written by Pablo to himself. The letter makes Antonio fall into a jealous rage, but he has to return to his native Andalusia, where he lives with his domineering German mother. As he promised, Pablo sends Antonio a letter signed Laura P, the name of a character inspired by his sister in a script he is writing. In his letter, Pablo tells Antonio that he loves Juan and intends to join him. However, Antonio, who is jealous and wants to get rid of Juan, gets there first. Antonio wants to possess everything that belongs to Pablo, and tries to have sex with Juan. When Juan rebukes his advances, Antonio throws him off a cliff. After killing his rival, Antonio quickly heads for his hometown. Pablo becomes a suspect in the crime because the police have found in Juan’s fist a piece of clothing that matches a distinctive shirt owned by Pablo. In fact, Antonio was wearing an exact replica when he killed Juan.

Pablo drives down to see his dead lover, realizes that Antonio is responsible for the murder, and confronts him about it. They have an argument and Pablo drives off, pursued by the police. Blinded by tears, he crashes his car injuring his head. He awakes in a hospital, suffering from amnesia. Antonio’s mother shows the police the letters her son received, signed Laura P. The mysterious Laura P becomes the prime suspect, but the police cannot find her. Antonio returns to Madrid and, in order to get closer to Pablo who is still in the hospital, seduces Tina who believes his love to be genuine.

To help her brother recover his memory, Tina tells him about their past. Born as a boy, in her adolescence she began an affair with their father. She ran away with him and had a sex change operation to please him, but he left her for another woman. When her incestuous relationship ended, Tina returned to Madrid, coinciding with the death of their mother, and got reunited with Pablo. Tina has been grateful with Pablo who did not judge her. Tina also tells him that she has found a lover. Pablo gradually begins to recover; he realizes that Tina’s new love is Antonio and that she is in danger. He goes with the police to Tina’s apartment where she is being held hostage by Antonio. Antonio threatens a bloodbath unless he can have an hour alone with Pablo. Pablo agrees and joins him. They make love and Antonio then commits suicide.

Cast

Eusebio Poncela as Pablo Quintero: a gay film director and writer. He has found professional success with a number of films with outrageous titles, but he is unhappy in his personal life since he feels his lover Juan does not love him the way he would like.

Carmen Maura as Tina Quintero: Pablo’s transgender sister. She is an actress with a dark past. Her failures with men have made her very vulnerable. She has recently been abandoned by her latest partner, a lesbian model. Tina’s two greatest loves were her father and her spiritual director.

Antonio Banderas as Antonio Benítez: He is an uptight young man from a conservative family. His father is a politician, his mother a very religious woman. He becomes obsessed with Pablo after watching his gay film The Paradigms of the Mussel. After having gay sex for the first time with Pablo, he falls in love with him.

Miguel Molina as Juan: Pablo’s regular lover. Aimless and unassertive, he does not love Pablo as much as Pablo loves him. For the summer, he decides to leave Madrid to join his family in the south of Spain to work in bar.

Manuela Velasco as Ada: Tina’s surrogate daughter. A precocious ten-year-old girl, she loves Tina who acts as her foster mother. Ada refuses to go back with her mother when she comes back to take her with her.

Bibi Andersen as Ada’s mother: She is a lesbian statuesque model who left Tina for a male photographer and now plans to move permanently to Milan.

Fernando Guillén as the Inspector: He is a liberal, who takes an easy approach to his work in contrast to his zealot son, the detective. (played by Guillén’s actual son)

Fernando Guillén Cuervo as the Detective: He is an uptight conservative, eager about his job.

Helga Liné as Antonio’s mother: A German by birth, she is a religious fanatic and a strict, overprotective mother. She gives misleading information to the police about Laura P.

Nacho Martínez as the Doctor: He takes a personal interest in Pablo and Tina’s well-being and tries to help them not only medically, but also to avoid the police.

Germán Cobos as Father Constantino: He was Tina’s confessor in the religious school where she studied when she was a boy. He sexually abused her when she sang in the church’s choir as a child. He advises Tina to forget the past.

Rossy de Palma as TV Host

Production

Though written before Matador, Law of Desire was produced after Matador’s international release. Law of Desire was shot in Madrid and Cádiz in the latter part of 1986. It was the first film that came out from El Deseo, the production company that Almodóvar formed in company with his younger brother Agustín and with which he has produced all his subsequent films.[2] It was the experience of working with the producer of Matador that led the path to the Almodóvar brothers to become producers following the model of selling the film before its release.[2] ″With my first five films I had the impression of having had five children with five different fathers and of always fighting with each one of them, since my films belonged to them, from a financial point of view, but also on an artistic level, that is, on the level of a conception″,[2] Almodóvar commented.[2]

The homosexual subject matter in Law of Desire made it more difficult to find funding for its production.[3] Initially, the brothers could not get support from the ministry of culture. It was thanks to the personal intervention of Fernando Méndez-Leite, the government representative for film production, that the ministry of culture gave 40 million pesetas to make the film and Lauren films contributed with 20 million and the rest from other sources.[3] The film was a most modest production, with a total budget of 100 million pesetas, less than Almodóvar’s previous film.

Commenting on Law of Desire Almodóvar stated that his intention was to make a film about desire and passion: “What interested me most is passion for its own sake. It is a force you cannot control, which is stronger than you and which is as much a source of pain as of pleasure. In any case, it is so strong that it makes you do things which are truly monstrous or absolutely extraordinary”.[4]

Images

Reception

Law of Desire, Almodóvar’s sixth film, premiered in Madrid on 7 February 1987. It was the most commercially successful Spanish film at the local box office in 1987, and it was the Spanish film of that year most widely distributed abroad surpassing Mario Camus’s The House of Bernarda Alba. Law of Desire toured many festival circuits. It won the award for best director at the Rio de Janeiro film festival; best new director at Los Angeles; the Teddy Award (1987) at the Berlin International Film Festival[5] and Best Film at the San Francisco International Gay and Lesbian film festival. In Spain it won Fotogramas de Plata as Best Film and the National award for cinematography for Carmen Maura for her performance as Tina; other awards for the film came from Italy and Belgium.

It took time for Spanish film critics to warm up to Almodóvar’s work. His earlier films were recognized for the irreverence of their humor and social parody but were generally deemed as frivolous. Law of Desire was better received than its predecessor. Ernesto Pardo writing for Segre wrote: I have never been keen on Almodóvar … I find him too over the top, excessive, unreal… As if he lived in another world… on the other hand [with Law of Desire, Almodóvar] has achieved what at the outset seemed impossible. That is, a more than acceptable film”.[6] In Cinco Dias Antonio Gutti criticized the film’s emphasis on the homosexual as too sustained and felt that Almodóvar’s irresistible humor did not appear.[6] Angel Fernandez Santos in El País considered that the film contained “such an excess of incidents and events that their sheer number neutralizes some of its quality”. In El Periodico, Jorge de Cominges commented that: “Pedro Almodóvar’s success is in putting together the different elements of such a wild story. In a quite brilliant manner he creates characters as impactful as the police detective and his son; and he turns the magnificent Carmen Maura into the most sensual woman you can imagine. Law of Desire is a film which is as satisfying as it is amusing. An outstanding achievement.” Manuel Hidalgo wrote: “Law of Desire is Pedro Almodóvar’s most homogeneous, controlled and finished film”.[6]

Pauline Kael in The New Yorker commented: “The film has the exaggerated plot of an absurdist Hollywood romance, and even when it loses its beat (after a murder) there’s always something happening. This director manages to joke about the self-dramatizing that can go on at the movies, and at the same time reactivate it. The film is festive. It doesn’t disguise its narcissism; it turns it into bright-colored tragicomedy”.[7]

In her review for The New York Times Janet Maslin said: “What it lacks in depth, Law of Desire makes up in surface energy, with a lively cast, a turbulent plot and a textbook-worthy collection of case histories”.[8] Jonathan Rosenbaum from Chicago Reader concluded: “The film bristles with energy and bright interludes before the lugubrious plot takes over…”.[9]

In his review for Time Magazine, Richard Corliss called the film “a bleak comic and defiantly romantic”. David Edelstein in New York magazine called it “a swirling Cri de Coeur [that] explores the conflict within a director between voyeurism and passionate love”.

Analysis and Influences

Law of Desire is anchored in the melodrama genre. However Almodóvar explained that the film did not follow the conventions of the genre: “In melodrama there have always been characters that are either good or bad, but today you can’t portray characters so simplistically. There aren’t good people and bad people, everything is more complex. Law of Desire is a melodrama which breaks the rules of the genre”.[10]

Almodóvar has spoken of his aspiration for the films of Francis Ford Coppola particularly in the way he mixes genres, such as in The Godfather which mixes gangster film and family drama.

The director also mentioned that it was influenced by the Hollywood melodramas of the 1940s and 1950s particularly those made by Douglas Sirk and Billy Wilder’s 1950 Sunset Boulevard, which he called “an epic film with regards to emotion”.

There is also the influence of the French writer Jean Cocteau, whose play The Human Voice (La Voix humaine) (1932), is adapted by Pablo Quintero. The work of Mexican poets in the early 1930s known as Los Contemporáneos, also presented in the work of Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca. Almodóvar refers to a Latin American sentimentality more openly melodramatic than in Spain as reflected in Almodóvar’s preference for choosing Latin American boleros for his films.

The outrageous titles of Pablo’s film seem to belong to John Waters’ aesthetic universe of pop culture, media, and trash as found in Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977). Law of Desire is closely linked to two of Almodóvar’s subsequent films. Religion and sexual abuse appear in the character of Ada who with Tina makes a cruz de mayo, a makeshift altar that mixes religious and pagan elements. Ada makes a vow of silence until certain wishes have been fulfilled. She also wants to make her first communion. The scene in which Tina enters her former school where she sang as the soloist at church and confronts Father Constantino, the priest who abused her when she was a boy, formed a partial genesis for Almodóvar’s later film Bad Education.

The character of Pablo serves as an alter ego for Almodóvar. Pablo is working on his new film whose main character is Laura P. The implausibility of its plot reflects the intricate and outrageous plot of Almodóvar’s own film. When she was left by one of her lovers, Laura ran after him and broke an ankle. She had her leg amputated, so that others would feel guilty, but even thus, her thirst for vengeance was not quenched.

In the video arcade scene in which Antonio tries to be seductive, he lights both his and Pablo’s cigarette. This is a reference to Bette Davis’s film Now, Voyager (1942) directed by Irving Rapper in which Paul Henreid puts two cigarettes into his mouth and lights one for Bette Davis.

Reinforcing the links between life and art, Ada’s mother has left Tina to elope with a photographer. Stage life and real but through law of desire Cocteau monologue talks of the separation of the expressive pore. Almodóvar cited American painter Edward Hopper as an inspiration for the way in which his cinematographer Ángel Luis Fernández photographed Madrid. Tina’s revelation of her torrid past to her amnesiac brother, although narrated but not shown, recalls Elizabeth Taylor’s outrageous claims in Suddenly, Last Summer, Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s 1959 adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s play.

References

- Rosewarne, Lauren (2014). Masturbation in Pop Culture: Screen, Society, Self. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-7391-8367-0 – via Google Books.

- Strauss, Almodóvar on Almodóvar, p. 63

- Edwards, Almodóvar: Labyrinth of Passion, p. 72

- Edwards, Almodóvar: Labyrinth of Passion, p. 74

- “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- Edwards, Almodóvar: Labyrinth of Passion, p. 73

- Kael, Pauline (12 April 1987). “Manypeeplia Upsidownia”. The New Yorker.

- Maslin, Janet (27 March 1987). “Law of Desire”. New York Times.

- “Law of Desire”. Chicago Reader. 26 October 1985.

- “Indiewire’s Law of Desire Review”. 9 November 2011.