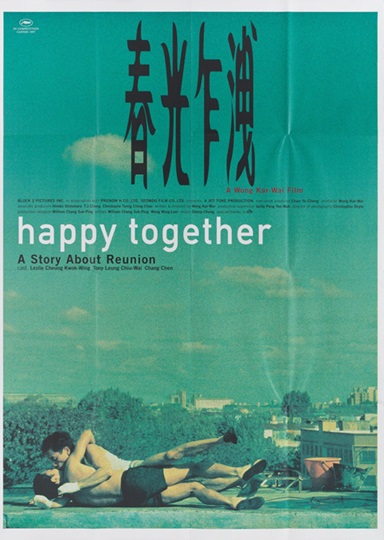

Happy Together (Chinese: 春光乍洩) is a 1997 Hong Kong romantic drama film directed by Wong Kar-wai starring Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-wai, depicting a couple’s turbulent romance. The English title is inspired by the Turtles’ 1967 song of the same name, which is covered by Danny Chung on the film’s soundtrack. The Chinese title (previously used for Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup) is an idiomatic expression suggesting “the exposure of something intimate”.[3][4]

The film was regarded as one of the best LGBT films in the New Queer Cinema movement and received critical acclaims and screened at several film festivals such as the 1997 Toronto International Film Festival; it was nominated for the Palme d’Or and won Best Director at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival.[5][6][7]

In 2022, Happy Together was ranked the 225th greatest film of all time in the Sight & Sound critics’ poll.[8] In 2016, the film was ranked the 3rd greatest LGBT film of all time in the British Film Institute poll.[9] In 2018, it was ranked the 71st greatest foreign-language film of all time in the BBC poll.[10]

Plot

Ho Po-Wing and Lai Yiu-Fai are a gay couple from Hong Kong with a tumultuous relationship marked by frequent separations and reconciliations. They visit Argentina together but break up after they become lost while traveling to visit the Iguazu Falls. Without the money to fly home, Fai begins to work as a doorman at a tango bar in Buenos Aires, while Po-Wing lives promiscuously, often seen by Fai with different men. After Fai accuses Po-Wing of spending all of his money and stranding him in Argentina, Po-Wing steals from one of his acquaintances and is severely beaten. Fai allows Po-Wing to live with him in his small rented room and cares for his injuries. They attempt to reconcile their relationship, though it is marred by mutual suspicion and jealousy.

Fai loses his job at the tango bar after beating the man who injured Po-Wing. He begins working at a Chinese restaurant where he befriends Chang, a Taiwanese co-worker. Later, Po-Wing and Fai have a final argument where Fai refuses to return Po-Wing’s passport. Po-Wing moves out of the apartment when he fully recovers. Sometime thereafter, Chang leaves Buenos Aires to continue his travels. Having finally earned enough money to fly home, Fai decides to visit the Iguazu Falls alone before he leaves. Meanwhile, Po-Wing returns to the empty apartment, heartbroken, realizing that Fai is gone for good.

Fai returns to Hong Kong but has a stopover in Taipei. Coincidentally, he ends up eating at a food stall in a night market run by Chang’s family. He steals a photo of Chang from the booth, saying that even though he does not know if he will ever see Chang again, he knows where to find him.

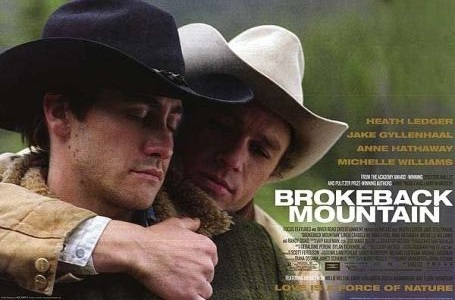

Images

Cast

Leslie Cheung as Ho Po-Wing

Tony Leung Chiu-Wai as Lai Yiu-Fai

Chen Chang as Chang

Release

Box office

During its Hong Kong theatrical release, Happy Together made HK$8,600,141 at the box office.[11]

Happy Together also had a limited theatrical run in North America through Kino International, where it grossed US$320,319.[12]

Censorship

The producers of the film considered censoring the film, specifically the opening sex scene for certain audiences.[13] Posters for the movie featuring the two leads fully clothed with their legs intertwined was banned from public places in Hong Kong and removed all together before the movie’s release.[14]

Home Media

Kino International released the film on DVD and Blu-ray on June 8, 2010. This release has gone out of print.[15]

The film was picked up by the Criterion Collection and released on March 23, 2021 on Blu-ray in a collection of seven Wong Kar-wai films.[16]

Trailer

Critical Reception

The film was generally well received in Hong Kong and has since been heavily analyzed by many Chinese and Hong Kongese scholars and film critics such as Rey Chow (周蕾) and 陳劍梅.[17][18]

A Hong Kong film review site called it an “elliptical, quicksilver experiment” that is “pure Wong Kar-Wai, which is equal parts longing, regret, and pathetic beauty” and applauding it for its cinematography.[19]

Due to the international recognition that the film received, it was reviewed in several major U.S. publications. Edward Guthmann, of the San Francisco Chronicle, gave the film an ecstatic review, lavishing praise on Wong for his innovative cinematography and directorial approach; whilst naming Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs amongst those who would have been impressed by his film.[20] Stephen Holden, of the New York Times, said it was a more coherent, heartfelt movie than Wong’s previous films, without losing the stylism and brashness of his earlier efforts.[21]

Derek Elley for Variety gave an overall positive review despite its lack of plot, calling it Wong’s “most linear and mature work for some time”. Elley praised the mise-en-scène, music, and William Chang’s production design. He emphasized that Christopher Doyle was the “real star” of the film for his grainy and high contrast cinematography.[13] Both Elley and Andrew Thayne for Asian Movie Pulse stated that both Leslie Cheung and Tony Leung Chiu-Wai excelled as the main characters in the film.[22]

However, Jonathan Rosenbaum gave the film a mixed review in the Chicago Reader. Rosenbaum, in a summary of the film, criticised it for having a vague plotline and chastised Wong’s “lurching around”.[23] In Box Office Magazine, Wade Major gave the film one of its most negative reviews, saying that it offered “little in the way of stylistic or narrative progress, although it should please his core fans.” He deprecated Wong’s cinematography, labelling it “random experimentation” and went on to say this was “unbearably tedious” due to the lack of narrative.[24]

As per the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 84% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 43 reviews, with an average rating of 7.40 out of 10. The site’s critics consensus reads: “Happy Together’s strong sense of style complements its slice of life love story, even if the narrative slogs”.[25] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 70 out of 100, with 71% positive reviews based on 17 critics, indicating “generally favorable reviews”.[26]

In 1997, Wong Kar-wai was already well known in the art house Chinese cinema world because of the success of his previous films: Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, and Ashes of Time. However, by winning the Cannes festival award for Best Director for Happy Together, his first major award, Wong was given a spotlight on the international stage.[27]

Music

In this film, Wong Kar-wai moved away from his previous centralization of American and British music, favouring South American music instead. This transnationalism “decentralizes America” and forms new connections between cultures that are not conventionally linked (Hong Kong and Argentina). The first song of the film, Caetano Veloso’s cover of “Cucurrucucú paloma”, a sad ballad about a man waiting for his lover to return, plays when the couple breaks up for the first time in the film. Here, the Iguazu Falls are seen for the first time and it is also the first shot of the film that is in colour. The song extends Fai’s thoughts, where he is imagining the waterfall, which he associated with Po-Wing. His sadness and lovesickness thereby become apparent in this South American setting.[28]

Musical motifs

The Frank Zappa song “Chunga’s Revenge” is played throughout the movie “emphasizing [Fai’s] difficult relationship with [Po-Wing].” The loud guitar chorus represents Po-Wing’s “volatile, flamboyant nature”, which contrasts the somber trumpet and slower beat representing Fai’s sensitivity and steadiness. This song is also linked to Lai’s loneliness and his longing to be “happy together” while showing the difference between the two characters and the increasing emotional distance between them as the film progresses.[28]

Astor Piazzolla’s “Prologue (Tango Apasionado)”, “Finale (Tango Apasionado)”, and “Milonga for Three” and similar bandoneon songs play when the couple is both together and apart, representing their relationship. These songs play during romantic scenes such as the taxi scene and the tango in the kitchen. However, it is also played after Fai and Po-Wing break up for the last time and Po-Wing dances the tango with a random man while thinking about when he danced with Fai. The last time this song is played is when Fai reaches the waterfall and the same shot of the Iguazu Falls at the beginning of the film is seen but this time with the “Finale” song. This “eulogizes that relationship” as Po-Wing breaks down in Fai’s old apartment, realizing that he has abandoned their relationship because Fai left behind the lamp while Fai mourns their relationship at the falls.[28] Wong Kar-wai discovered Piazzolla’s music when he bought his CDs in the Amsterdam airport on his way to Buenos Aires to film this movie.[29]

“Happy Together”, the Turtles’ song covered by Danny Chung, is the last song to be played in the film, when Fai is on the train in Taipei. This song is used to subvert Western music tropes that use it “to celebrate a budding romance or as an ironic commentary on the lack of such a romance.” It also shows that “Lai is at peace with their relationship, making it a crucial narrative device denoting the meaning of the film.”[28]

While interpretations vary, Wong Kar-wai has said that:

“In this film, some audiences will say that the title seems to be very cynical, because it is about two persons living together, and at the end, they are just separate. But to me, happy together can apply to two persons or apply to a person and his past, and I think sometimes when a person is at peace with himself and his past, I think it is the beginning of a relationship which can be happy, and also he can be more open to more possibilities in the future with other people.”[30]

Themes and Interpretations

Nationality, belonging, and cultural identity

At the very beginning of the movie, Wong includes shots of Fai’s British National Overseas Passport as a way to indicate to the audience that this film will be dealing with issues of nationality.[31]

The Handover of Hong Kong

Released in May 1997, intentionally before the handover of Hong Kong from the British to China on 30 June 1997 after 100 years of colonial rule, the film represents the uncertainty of the future felt by Hongkongers at the time.[32][3] The film’s subtitle: “A Story About Reunion” also implies that the film would comment on the handover.[33] The inclusion of the date in the opening and the news broadcast of Deng Xiaoping’s death on 20 February 1997 serve to place the audience explicitly in the time period immediately before the Handover of Hong Kong. Some have suggested that the English title of the film is in relation to the uncertainty around if Hong Kong and China would be “happy together” after their reunion.[33]

In one interpretation, Po-Wing and Fai represent two sides of Hong Kong that cannot be reconciled: Po-Wing stays in Buenos Aires without a passport, like Hong Kong Chinese people who don’t have a real British passport, representing an “eternal exile and diaspora”. Fai, however, is able to see the waterfall and go to Taiwan but it is not shown whether Fai is able to reconcile with his father or not. Since Po-Wing wants his passport, meaning he wants to leave Buenos Aires, both main characters show that they feel uncertain about their place in the diaspora.[34]

A different interpretation stated that Fai, a gay man, represents the social freedoms that Hongkongers possess and the runaway son who travelled to the other side of the world: Buenos Aires in the film and Britain historically. But, this son (Hong Kong and Fai) “must return and reconcile his differences with old-fashioned China,” which is represented by Fai’s father. Chang represents Taiwan, a country with a similar past as Hong Kong with China, who comforts Fai (Hong Kong), showing him that there is hope for the future. This hope is demonstrated through the increasing saturation of the film as Fai’s life becomes more and more stable.[22]

Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Buenos Aires

Wong’s choice of Buenos Aires is particular because it is the antipode of Hong Kong, meaning it is on the opposite side of the world and in an opposite time. This had been interpreted as a place where Fai and Po-Wing were looking for the opposite of home and Hong Kong. They do not describe this as a political allegory but rather a questioning of cultural identity and the definitions of “home, belonging, and migrancy”.[33] Another interpretation viewed the scenes of Hong Kong shot upside down not as a political allegory either, but a way to show how far the characters were from their roots.[31]

Similarly, the theme of displacement from Hong Kong to Buenos Aires interestingly emphasizes their similarities rather than their differences when compared to the shots of Hong Kong in Wong Kar-wai’s previous films. Despite being on the other side of the world and far from their “home”, the couple experiences the same problems, implying the inevitability of their relationship’s deterioration. By emphasizing the similarities between these two places, Wong emphasizes the homelessness and lack of belonging of both Fai and Po-Wing.[33]

Confinement

Another theme of the film is the sense of confinement and claustrophobia that accompanies the sense of non-belonging of Fai and Po-Wing. This is conveyed through the shaky handheld camera, the small size, poor lighting, and dirtiness of Fai’s apartment, the kitchen, alleys, the tango bar, the restaurant kitchen, and the public bathroom corridor. This confinement is also manifested through Po-Wing’s confinement to Fai’s apartment because his injured hands prevent him from taking care of himself. Later, Po-Wing is also confined to Buenos Aires because Fai refuses to return his passport. Yet, the imagery of the Iguazu Falls contrasts the theme of confinement with the symbolic openness of possibility and hope for Po-Wing and Fai’s relationship.[33]

Marginalization

One interpretation explained that the lack of a sense of belonging due to a combination of their marginal race, sexuality, and language[31] in Buenos Aires and Hong Kong prevented Po-Wing and Fai from forming a stable relationship. This instability is in part shown through the instability of the camera in some shots, relating to the characters’s inability to find their own place in the world.[22] Neither place is welcoming and the couple experiences the same problems in both places.[32]

The marginalization of Fai specifically is demonstrated by the way he visually cannot blend into the crowds and environments in Buenos Aires in comparison to Taipei. It is only in Taipei that Fai smiles, and it is implied that he feels a sense of belonging as he visits the Chang family noodle shop and takes the train. The movie does not definitively show that Fai returns to Hong Kong, making it possible that he stayed in Taipei, where he feels like he belongs and begins to have hope for the future.[31]

The Iguazu Falls and the lamp

The importance of the Iguazu Falls is established early on in the film when it is shown on the lamp that Po-Wing bought for Fai and is said to be the entire reason the couple chose to go to Buenos Aires in the first place.[33] The real waterfall is then shown in Fai’s imaginings after the first breakup as the first shot in colour. It is also shot from a bird’s-eye view and given unrealistic blue and green colouring, giving it a supernatural visual effect.

One scholar interpreted the representation of the falls as a contemplation on the immensity of mother nature’s power and the unpredictable nature of the future since the end of the waterfall is imperceivable. It also evokes a feeling of powerlessness in the face of nature and the future, paralleling the inevitability of the deterioration of Po-Wing and Fai’s relationship[18]

Another scholar interpreted the waterfall itself as a symbol of Po-Wing and Fai’s relationship because “their passion is indeed torrential, destructive, always pounding away as it falls head forward and spirals downward towards an uncertain end”.[35]

The falls are seen throughout the film on the lamp in Fai’s apartment, representing the continued hope and investment in his relationship with Po-Wing. However, when Fai finally visits the Iguazu Falls but without Po-Wing, leaving the lamp behind, Po-Wing understands that Fai has finally abandoned their relationship. Both Fai and Po-Wing mourn their relationship by looking at the waterfall, Fai seeing it in reality, and Po-Wing after having fixed the lamp’s rotating mechanism.[28]

Homosexuality

The portrayal of homosexuality in the film is indisputable. On one hand, it is characterized as “one of the best films chronicling gay love ever made” because of the universality of the problems that Fai and Po-Wing face in their relationship that exist in any relationship no matter the gender of the participants.[36] Many scholars and film critics agree that while being gay is not the subject of the film, its portrayal of gay romance is realistic.[37] The film was praised for not casting the characters on gendered lines, questioning their manliness, and showing the complexity of gay men as social beings and individuals.[7]

Wong Kar-wai explained that:

“In fact, I don’t like people to see this film as a gay film. It’s more like a story about human relationships and somehow the two characters involved are both men. Normally I hate movies with labels like ‘gay film,’ ‘art film’ or ‘commercial film.’ There is only good film and bad film.”[7]

On the other hand, some scholars argue that one of the reasons that Po-Wing and Fai ended up in Buenos Aires is because they are gay and are thus exiled homosexual men.[28] Jeremy Tambling, an author and critic, noted that the universalization of the gay relationship is not a positive aspect of the film because it erases the specificity of their experiences and the film’s theme of marginalization.[3] Furthermore, the film broadly portrays neo-Confucian values of hard work, frugality, and normativity, emphasizing social conformity to Chinese working values. Fai is rewarded for following these values, as he works constantly, cooks, cares for others, wants to reconcile with his father, and saves his money, while Po-Wing lives in excess through his numerous sexual encounters, spending, lack of traditional work, and flamboyance. At the end of the film, Fai is able to reach his destination, Hong Kong/Taiwan and the Iguazu Falls, while Po-Wing is stuck in Buenos Aires. Chang also represents these values, as he works hard at the restaurant, saves enough money for his trip to the ‘end of the world,’ and has a loving family to return to in Taipei. The characters who conform to this normativity are rewarded while others are punished, thus emphasizing a narrative wherein gay men “succeed” when conforming to other cultural etiquettes unrelated to their sexualities.[38]

Legacy

Since its release, Happy Together has been described as the “most acclaimed gay Asian film”, remaining in the public consciousness.[39]

South African singer, songwriter, and actor Nakhane cited Happy Together as one of their three favourite films of all time.[40]

James Laxton, the cinematographer for the critically acclaimed film Moonlight (2016), explained in a Time article that he was inspired by Happy Together and another Wong work, In the Mood for Love (2000). The use of natural and ambient light mixed with small warm fill lights, as well as touches of colour enlightened Laxton to create a “dream-like sense of reality” in his film. More specifically, he cited the scene where Chiron’s mother scolds him and the pink light emanates from her bedroom as particularly inspired by Wong Kar-wai’s works.[41]

The 2006 Russian sitcom Happy Together took its name from the name of the film.[42]

At the 2017 Golden Horse Awards, Happy Together was re-screened in celebration of the film’s 20th anniversary. The main promotional poster for the award ceremony used a screenshot from the film of the main actors as well as shots of the Iguazu Falls.[43]

At the 2022 Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema, Happy Together was re-screened in celebration of the film’s 25th anniversary.[44][45] Rolling Stone magazine called this a “non-official protagonist of the festival”, since the debut documentary film, BJ: The Life and Times of Bosco and Jojo, was premiered in the festival (“Special Nights” section), narrating the encounter with the Hong Kong filmmaker.[46]

References

- “Happy Together”. BBFC. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- “Happy Together (1997)”. Box Office Mojo. 2 December 1997. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Tambling, Jeremy. (2003). Wong Kar-wai’s Happy Together. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8053-35-3. OCLC 1032571763.

- Tony Rayns. “Happy Together (1997)”. Time Out Film Guide. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008.

- “Development of the New Queer Cinema Movement”.

- “Festival de Cannes: Happy Together”. festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- Lippe, Richard (1998). “GAY MOVIES, WEST AND EAST: In & Out: Happy Together”. Cineaction (45): 52–59. ISSN 0826-9866.

- “The Greatest Films of All Time”. BFI. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- “The 30 Best LGBTQ+ Films of All Time”. BFI. 15 March 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- “The 100 greatest foreign-language films”. BBC CULTURE. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- “1997 香港票房 | 中国电影票房榜” (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- “Happy Together (1997) – Box Office Mojo”. boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Elley, Derek (25 May 1997). “Film Review: Happy Together”. Variety. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- “When Wong Kar-wai’s gay film Happy Together won big at Cannes”. South China Morning Post. 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- “Happy Together Blu-ray (春光乍洩 / Chun gwong cha sit)”.

- “World of Wong Kar Wai Blu-ray (DigiPack)”.

- 精選書摘 (18 July 2019). “《溫情主義寓言・當代華語電影》:《春光乍洩》愛慾關係轉成深深鄉愁”. The News Lens 關鍵評論網 (in Chinese). Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- “【黑色電影】《春光乍洩》:身份意識的切換與探索”. 橙新聞. Retrieved 23 March 2020.[permanent dead link]

- “Happy Together (1997)”. lovehkfilm.com. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Edward Guthmann (14 November 1997). “Misery Loves Company in ‘Happy Together'”. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- “Help – The New York Times”. Movies2.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Thayne, Andrew (28 August 2019). “Film Review: Happy Together (1997) by Wong Kar-wai”. Asian Movie Pulse. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Champlin, Craig. “Music, movies, news, culture & food”. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 14 July 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- Sparktech Software LLC (10 October 1997). “Happy Together – Inside Movies Since 1920”. Boxoffice.com. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- “HAPPY TOGETHER”. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- “Happy Together”. Metacritic. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- “In pictures: Wong Kar-wai’s romantic film Happy Together turns 20”. South China Morning Post. 14 May 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Kersting, Erik (2018). East, west, and gendered subjectivity : the music of Wong Kar-Wai. ISBN 978-0-438-03277-4. OCLC 1128098058.

- Wong, Kar-wai (2017). Wong Kar-Wai : interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-1284-1. OCLC 1023090817.

- Wong Kar-wai (27 October 1997). “Exclusive Interview” (Interview). Interviewed by Khoi Lebinh; David Eng. WBAI. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

- “埋藏在《春光乍洩》裡的時代情緒 | 映畫手民”. cinezen.hk. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Aw, Tash (3 September 2019). “The Brief Idyll of Late-Nineties Wong Kar-Wai”. The Paris Review. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Suner, Asuman (2006). “Outside in: ‘accented cinema’ at large”. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 7 (3): 363–382. doi:10.1080/14649370600849223. hdl:11693/49209. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 145174876.

- Berry, Chris (24 October 2018), “Happy Alone? Sad Young Men in East Asian Gay Cinema”, Queer Asian Cinema: Shadows in the Shade, Routledge, pp. 187–200, doi:10.4324/9781315877174-7, ISBN 978-1-315-87717-4, S2CID 239905480

- Chung, Chin-Yi (2016). “Queer love in Wong Kar Wai’s Happy Together (1997)”. Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture. 16 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Nochimson, Martha P. (2005). “Beautiful Resistance: The Early Films of Wong Kar-wai”. Cinéaste. 30: 9–13.

- Royer, Geneviève (September 1997). “Happy Together”. Séquences: 26–27.

- Yue, Audrey (2000). “What’s so queer about Happy Together? a.k.a. Queer (N) Asian: interface, community, belonging”. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 1 (2): 251–264. doi:10.1080/14649370050141131. hdl:11343/34306. ISSN 1464-9373. S2CID 53707294.

- “7 beautiful Asian movies that celebrate LGBTQ+ romance”. South China Morning Post. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- “NAKHANE. on Instagram: “This is one of my top 3 of all fucking times. Happy Together by Wong Kar-wai. We stole so much from it for my ‘Clairvoyant’ video.””. Instagram. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- “Behind the Making of the Oscar-Nominated Film ‘Moonlight'”. TIME.com. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- VanHooker, Brian (22 October 2021). “AN ORAL HISTORY OF ‘СЧАСТЛИВЫ ВМЕСТЕ,’ THE RUSSIAN REMAKE OF ‘MARRIED… WITH CHILDREN'”. MelMagazine. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- DFUN. “2017金馬主視覺 向電影《春光乍洩》致敬! – DFUN” (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Festival, Asian Film (8 April 2022). “23rd BAFICI Buenos Aires International Independent Film Festival – Asian Presence”. Asian Film Festivals. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- “Función especial 25 años de “Happy Together””. Buenos Aires Ciudad – Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ARMENTANO, BARTOLOMÉ (14 April 2022). “BAFICI 2022: qué películas no te podés perder”. Rolling Stone en Español (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 November 2022.

Where to Watch or Buy – as of 06/30/24

Happy Together (1997)

Amazon – Prime – Visit Prime

Stream – Criterion Channel, VIKI (Ads)

Rent – Apple TV, VUDU

DVD – Visit Amazon Here